University of Oregon Professor and SEAMUS 2006 Conference Host Jeff Stolet conducted the following interview with former SEAMUS President (1989 – 1996) Scott Wyatt, an admired and respected composer, teacher, and champion of electronic music for decades through his service to SEAMUS and as Director of the Experimental Music Studios at UIUC.

—Scott Wyatt

(Jeff Stolet prepared the following introduction and then posed the questions that Scott answers below.)

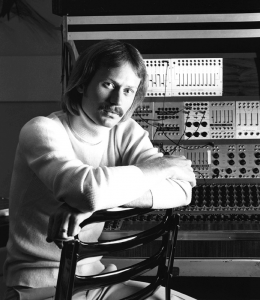

Professor Scott Wyatt has been a faculty member at the University of Illinois School of Music for 40+ years teaching composition, theory, and electroacoustic music, as well as serving as director of the University of Illinois Experimental Music Studios. He is an acclaimed, award-winning composer whose music is admired around the world. Among his compositions are Counterpoints (1992), Time Mark (1989), A Time of Being (1996), Private Play (1997), In the Arms of Peril (2001), Night Visitors (2002), On a Roll (2004), A Road Beyond (2007), and (2010), all of which were selected to be on the SEAMUS Series CD. Professor Wyatt is one of my musical heroes, so it is a great honor and privilege for me to ask him a few questions and to learn from his replies. Scott, thank you so much for consenting to respond to my musical inquiries.

Professor Scott Wyatt has been a faculty member at the University of Illinois School of Music for 40+ years teaching composition, theory, and electroacoustic music, as well as serving as director of the University of Illinois Experimental Music Studios. He is an acclaimed, award-winning composer whose music is admired around the world. Among his compositions are Counterpoints (1992), Time Mark (1989), A Time of Being (1996), Private Play (1997), In the Arms of Peril (2001), Night Visitors (2002), On a Roll (2004), A Road Beyond (2007), and (2010), all of which were selected to be on the SEAMUS Series CD. Professor Wyatt is one of my musical heroes, so it is a great honor and privilege for me to ask him a few questions and to learn from his replies. Scott, thank you so much for consenting to respond to my musical inquiries.

Q1: Let’s begin with a fundamental question. What is music?

For me, I consider music as being creatively organized sounds in time, combined to form artistic and dramatic expression, with more successful music incorporating a composed structure, flow, direction, progressive development, and drama. Music exists in many hybrid forms, and within a changing world having many diverse opinions, its definition lies with the individual; the composer, performer, conductor, producer, and listener.

With no malice intended, I differentiate music from sound art because of my composer preferences as listed above. These characteristics are often not the main concern of sound art, where space (and sometimes sound) rather than time, is emphasized.

The term sound art is often used for practices of sound installations, some performance art, as well as sound sculptures, which are all valid art forms. William Hellerman supposedly first used the term in the early 1980’s for a show he organized in New York, although I’m sure it has strong roots from the Futurists’ fascination with noise and machines, and with breaking the boundaries of the past. To paraphrase Max Neuhaus’ and Carsten Seiffarth’s definitions, sound art is an exploration of sound in a unique space, and of the relationship of sound to and in a specific context of its hearing, thus turning space into place. Here is where definition and distinction become blurred especially with acousmatique music.

There is no right or wrong here, just personal preference, and I prefer working with music composition rather than sound art.

Q2: Given your response above, what is electro-acoustic music and how does it provide a vehicle for what you do creatively?

Electro-acoustic music, within the context of contemporary concert art music, refers to a genre of music, whose compositional idea is specifically composed to require specialized electronic means for its sonic creation, assemblage, and presentation — that could not be created in any other manner.

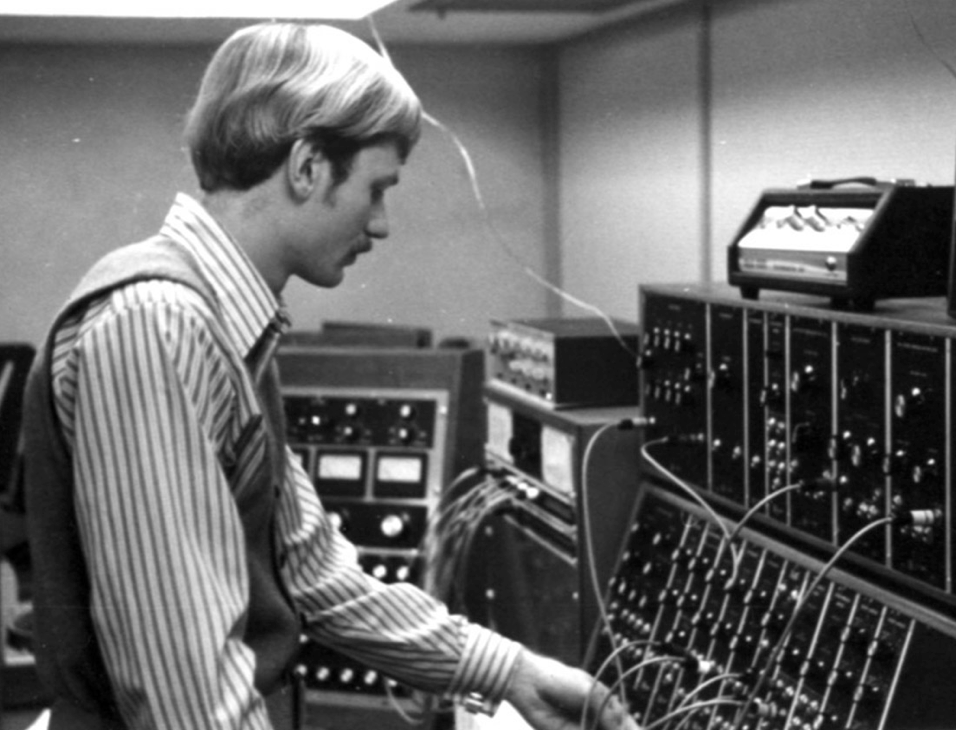

I studied classical piano as a child, but soon began living a double life of playing keyboards and bass in rock bands (as the Beatles and the Byrds dominated much attention at this time) during middle school and high school, while still studying classical piano. My family didn’t have money, and so I learned to build speaker cabinets and amps to have access to gear. I was always fascinated with technology and music, and so for me, I was drawn to both the music and the equipment when I began hearing about “electronic music” while still in high school. In 1964 Bob Moog and others, such as James Beauchamp, Don Buchla, and Alan Pearlman, had introduced the modular voltage-controlled synthesizer and an excitement was in the air. While in high school, my only awareness of synthesizers was with their commercial and entertainment industry use, along the lines of Wendy Carlos’ Switched On Bach, the Beach Boys, the experimental band Organisation (later called Kraftwerk), and Jean-Michel Jarre’s early efforts. By 1970, I was a freshman in college at West Chester University studying music education and piano performance. Here I was given access to a new Moog Series 900 modular synth that had no manual! At that time, no one there knew how to use it. Fortunately, I had enough experience with bands and building equipment that I began trying to figure out the beast by writing up a user manual for both faculty and students. Keep in mind this was before the Internet. Information had to be obtained the old fashioned way. I was simultaneously introduced to the music of Babbitt, Cage, Hiller, Subotnick, Stockhausen, Varese, and Xenakis, which for me, was a different kind of excitement, and I wanted to find out how and why this creative form existed. This music was foreign to me, yet I was very much drawn to it. In my sophomore year, my composition teachers at that time included Larry Nelson and John Melby, who challenged me compositionally and musically. I was fortunate to have access to a fairly large studio complete with army surplus microphones, the Moog, two Scully two-tracks, and a Scully half-inch four-track, that gave me opportunities to explore both concrète and synthesis. In the long run, this degree of enthusiasm, exposure to new music composition, aesthetic challenges, and access to technology, and its inherent problems, launched me into a long relationship and career.

Skipping over several decades to today, I enjoy the challenge of working with technology and attempting to create a work that does not sound as if it was created easily. Technology has advanced to the point that it produces good sound quality easily in comparison to the early days. Many students and composers new to electroacoustic music are drawn to the accessibility and the ease of generating output. This, coupled often with a lack of investigation of what determines art status and even higher audio quality production, results in many elemental compositions and performances. I have tried to combat this by continually challenging my students and myself, to avoid the obvious and the elemental, with respect to concert art electroacoustic music works. Electroacoustic music has satisfied my desire to work with art music and technology.

Q3: In your 1998 article “Gestural Composition”[1] you describe the design and use of sonic gestures along with their transformation and development as a basis for an electro-acoustic composition. Can you take us through your thinking about sonic gestures that culminated in that article and also any evolution that your ideas have under went during the past seventeen years? In addition, do you regard the gesture as you describe in this article as a central element of your compositional method?

In order to answer your question, I have to refresh my memory and reread part of the article. The article states, “many American electro-acoustic works are often concerned with the use of pitch as one of the primary compositional focal points. While I consider this a valid approach, I have been interested in the design and use of sonic gestures that are not immediately based upon pitch as the obvious focal point. These gestures can be concrète and/or electronically generated, and I have no prejudices for either, that are much further processed and shaped electronically to create new identities that transform and develop throughout the designed course of the composition. This approach, with its roots in both traditional concrète and synthesis techniques, takes on a time-based sculptural performance that affords the listener a desired opportunity to discover the interplay and development of molded sonic events, without the interference of pitch as the primary factor. Attention turns to gestural evolution and gestural development within a host space or spaces. Some have labeled this approach “gestural composition” or “sound mass composition,” and while other approaches are often pursued within the University of Illinois Experimental Music Studios, “gestural composition” has maintained a major presence during the Studios’ 50+ year history.”

All too often, I hear a lack of clearly defined compositional motives and very little progressive development of these motives within electroacoustic music works. For me, the presentation of clear motivic gestures and their evolution through progressive development promotes more than just the sounds; it advances the work itself with an evolving energy, motion, direction, and the composed drama beyond that of the original sound objects. This remains a central concern for my compositional approach.

Q4: It appears to me that a great deal of the initial material of your compositions originated as sound from our acoustic world. Can you comment on your preference of using sampled audio as the basis of so many of your compositions?

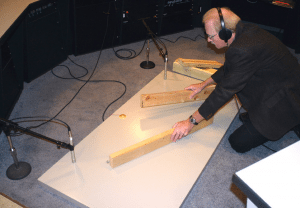

Early in my career, I spent a great deal of time with sound synthesis, not only through my initial work with the Moog, and later, the Buchla synthesizer, but also with sound synthesis programs Music 4BF, Music 360, and later with MIDI driven by Vision and Digital Performer sequencer software. Almost all of my early works were synthesis based. I began to embrace concrète as a way of exploring sound by looking for and harnessing the natural energy that lies within an acoustic sonic event. Currently, I record all of my initial sonic material within a studio setting to capture and sculpt as much of the life of the sound as possible rather than working with downloaded samples. Trying to discover the essence of the characteristic gesture of a sound is a revealing and an exciting process. It leads to further future discovery and compositional opportunities. I endeavor to record sounds and capture the sonic essence with what I consider to be the highest quality which is determined by mic selection, placement, and positioning through careful monitoring. At times, achieving high quality does not involve the most expensive mics or the highest sample rate or bit rate, but more careful listening, good recording techniques, and some unorthodox recording approaches. I record generally at 44.1 kHz / 16 bit to avoid having to go through a conversion process. Capturing the lifeblood of the sonic moment is the key, and very much part of the chase. This discovery process often leads me to carefully alter the sound later in an effort to accentuate the gestural characteristic of the sound. In thinking about this approach now, I believe my time with synthesis has given me experience to sculpt and process my recorded material.

Q5: I spent a year and a half in Eugene, Oregon working out at a local health club to a playlist of your compositions. When I hear your music the impeccable balance between the musical elements, the detailed spatialization, the musical nuances that are revealed, and the sheer amount of time within each composition that I, as the listener, am placed in a state of musical anticipation, I am completely awed. The anticipatory moments often lead to spectacular and satisfying articulatory moments. Please describe for us how you think about the creation of these musical elements?

My dear Jeff – we need to work on your playlists for the gym!!!

I begin by sketching out a basic structure based upon whatever idea is behind the work. I endeavor to clearly define all aspects of the compositional idea(s) including contrasting motives, a developmental plot, and potential dramaturgy. After recording my initial material and going through a discovery process of altering them through an array of hardware and software, I begin assembly of the skeletal framework through to the end of the piece, within a stereo context. I revisit the structural design, existing temporal activity, various twists and turns of the plot, any dramatic extensions and shifts, and spatial designs. Much of this is done on paper against the timeline of the work. While some of my works incorporate an

underlying narrative, all of my compositions revolve around the energy and pure development of the gestures and motives. The developmental activity needs to present the listener with a sonic rollercoaster ride of unexpected shifts and drama, while also having concern for continuity of presentation. I then attempt to engineer/realize sound movements (translations), the many shifts of environments, and juxtapositions of depth proximities that often take many hours of studio time. I have found this actually requires a well-designed studio with very reliable monitoring at consistent listening reference levels. Any sounds that move within the space must initially imply such movement, and for me, this is engineered manually rather than using any multi-channel panners, and characteristics of the movement often need to be exaggerated. Additional attention is required to prevent other sounds and sonic events from masking the main sonic translations. The engineering of the sound translations and various host environments have to be believable. Too many times composers’/engineers’ intent is not realized effectively. It is worth striving for this level of achievement.

Q6/7: Is there a musical work that most influenced your technical approach to the composition of electro-acoustic music? Along the same lines, what composition inspired your musical work the most?

My guess is that I have been influenced by a variety of works and composers for musical elements, compositional design, spatial exploration, and engineering prowess. A few earlier works that come to mind include Morton Subotnick’s Touch (1969) because of his pioneering four-channel sound design, control signal process, and synthesis work, John Chowning’s Turenas (1972) with his amazing simulated Doppler shifts and depth proximities, and Lars-Gunnar Bodin’s For Jon, Fragments of a Time to Come (1977) with its intriguing narrative and very high quality engineering. Some of the spatial translations created by Salvatore Martirano with his 24-channel Sal-Mar Construction (1972-75) also inspired me with my early research and initial engineering attempts with spatialization. Herbert Brün’s SAWDUST series (1976-78) drew remarkable focus to gesture and progressive development of gesture. Mario Davidovsky’s Synchronisms greatly influenced my compositional thinking with my instrumental compositions involving electroacoustic accompaniment. Mid-career strong influences came from discussions I had with Kevin Austin of Concordia University and with Jonty Harrison of the University of Birmingham (UK) concerning diffusion and spatialization aesthetics and practice. This, and the overall influence of the electroacoustic masters, my past teachers, my colleagues at the University of Illinois and within SEAMUS (including your music – Jeff!), and many of my students, has motivated me to continually expand and refine my compositional and engineering abilities.

Q8/12: Do you have any routines or preparatory rituals that you employ to help you perform your compositional work? Are there special conditions you create for yourself to establish the most favorable environment in which to compose? Do you mine philosophy or other arts as inspiration for your musical creations?

Well – deadlines are motivational!! I never really had dedicated creative time due to the constraints of my University position supervising and managing our large studio facilities and the usual teaching overload that demanded even more time commitment. For me, I had to learn efficiency and focus. All of this was very much a balancing act between family, the University job, and career pursuits. I am sure you have experienced this continuing saga. I found that compositional motivation is enhanced when some extra musical idea or notion that strongly interests me, becomes a driving force that propels me to want the composition to exist. This could mean the composition is programmatic, at least for the composer, or that there is an idea fostering the compositional elements, design, and/or structure that is the raison d’être for the piece’s creation. This was the approach taken with A Time of Being (1996) dedicated to the memory of those who perished on that day at the Oklahoma City bombing, In the Arms of Peril (2001) presenting a sense of impending danger just prior to 9-11, …and nature is alone (2005) in memory of the victims of the Chernobyl accident on the 20th anniversary of the disaster, A Road Beyond (2007) created in response to the death of a close friend, All At Risk (2004) concerning the Iraq War, and ComLinks (2010) where I offer a sonic commentary on our so-called connected society. I spent time researching the subject at hand, defining terms, defining plots and subplots, storyboarding, and considering elements of drama prior to working with notes and/or sound. This degree of preparation assisted me with efficiency and focus for both composition and studio realization.

Q9: You’ve shared a number of things with us, can you tell us what you think makes a musical composition a success?

Well, my question in response would be: from whose perspective: the composer, the performer, or the audience?

My best answer to you is that I gauge the degree of success for my own compositions based on the comments and reactions received from my colleagues in the field and those reactions of my students whom I feel are both informed and experienced. I also count general audience reaction in this overall mix. Obviously, I have to sign off on the quality of my own work, but I also have to keep in mind the overall reason why we create. It is both a personal and social act. We create because we want to, but most of us also want our creations heard, and in some cases, also seen. This sense of exhibiting our creations through public performance allows us to display our wares, as well as share the end result within a social context that is very different from individual listening. The collective reactions we receive from our colleagues and audience members provide us with additional information we can use to determine the success of our creation beyond our own perspective, which is valuable information.

Q10: Which of your electro-acoustic compositions do you find most satisfying?

This is difficult to answer, as most of my works have a very different focus. Some of my earlier works remain close to me due to the amount of time they took to realize, involving very old-school techniques. Time Mark, for solo percussionist with electroacoustic accompaniment, has been a favorite due to the interplay between the percussion part and the accompaniment along with part of the accompaniment being positioned behind the audience. In the Arms of Peril was a response to the tension I felt within the country just prior to 9-11 – it is now dedicated to the many victims. On a Roll took more than 1000 hours to realize but was very effective with spatialization and 3D encoding in the long run. All At Risk, for video with 5.1 electroacoustic accompaniment, still receives a remarkable response from audience members as they read riveting email from a news correspondent friend embedded with military during the Iraq war. Perhaps one of my favorites is All Sink featuring the playful sounds of my dishwashing skills – don’t let my wife know…

Q11: What’s the most challenging aspect of creating a fixed media electro-acoustic composition?

Creating energy; making the sounds, the gestures, the environments, the performance itself come to life through both composition and engineering. I work very hard to create extra energy especially with fixed media works.

Q13: I found it rather striking that as a Professor Emeritus at the University of Illinois that you still listed your teachers in your professional biography. Can you talk about what your instructors meant to you in terms of what they taught you and how you have employed what you absorbed from them?

It has been my experience that many people do not express “gratitude” to others. I am truly thankful for the time my teachers spent with me and for their knowledge passed on during the many lessons. To this very day I am sincerely appreciative of their teaching, their time, their influence, and their support of my effort both during school and long after I graduated. All of them played a strong influential role in my development. These teachers include Richard M. Smith (Audubon High School – helped me initiate a strong passion for music), Larry A. Nelson (West Chester University – helped ignite my strong interest in composition, orchestration, and synthesis technology), John Melby (West Chester University and University of Illinois – taught me serial composition techniques and computer music composition), Herbert Brün (University of Illinois – offered discussions and lessons about gestural composition, cybernetics, and misuse of language), Ben Johnston (University of Illinois – introduced me to just-intonation), Salvatore Martirano (University of Illinois – offered discussions and lessons on the music and compositional techniques of Dallapiccola), and Paul Zonn (University of Illinois – offered composition lessons plus a strong focus on orchestration techniques).

Q14: Aside from the economic factors, can you tell us why you teach and what you enjoy the most about teaching?

I have always enjoyed teaching and working with students. For me it has always been enjoyable to exchange ideas and knowledge, and to get to know them on a personal level. While we may have had some similar experiences, I welcome the differences. I try to present myself as being open, personable, and caring individual, and not better than anyone else in the room. I approach them as colleagues, and that we all have something to offer to each other. While there has always been subject matter and information to present, getting them involved with the creative process, interpretation, decision-making, and problem solving with the hands-on projects has allowed them to approach creativity, technology, aesthetics, and professionalism at a very personal, individual, and real level. I shared many of my own experiences and compositions with them to show both problems and successes, as I have always wanted my creative output to display the attributes we discussed in classroom conversations. It has always been my hope they would realize the amount of dedication and hard work that is behind a creative work at this level.

Q15: You have a number of accolades, but what do you want your legacy to be

Overall I have been a very small cog in a rather large wheel, and so I think my influence has been minimal in the grand scheme of our world of electroacoustic music, however I do hope that I have brought about a more involved level of awareness of and commitment to musicianship, artistry, and professionalism that could and should be part of these creative works. I have experienced so many changes in technology during the course of my career, and today, the technology is very accessible and permits cool sounds to be achieved easily, yet all too often, elemental ideas and/or experiments are presented as being a work of art. It is my hope that we raise the bar of what art can and should be, and challenge ourselves to meet this objective. This has been a part of my message passed on to my students and colleagues – perhaps this message could be part of my legacy…

P.S. Q15.5: You drive a yellow Corvette, please tell us about your interest (obsession) in fast cars? ?

P.S. Q15.5: You drive a yellow Corvette, please tell us about your interest (obsession) in fast cars? ?

I always wanted to get to work quickly, and then after the long day at work, boogie on home, while enjoying the driving experience… After all of these years, patience, at the end of the day, still eludes me.