SEAMUS Member At Large Eli Fieldsteel interviews his former teacher and past SEAMUS President Russell Pinkston

“With every advance in technology, new possibilities are opened, even as some things we may have valued highly may seem to be lost. And the new possibilities tend to allow composers to work at a higher level, which then introduces a whole new set of techniques and problems that we hadn’t had to deal with before, either as composers, or as teachers.”

— Russell Pinkston

Intro by Eli Fieldsteel:

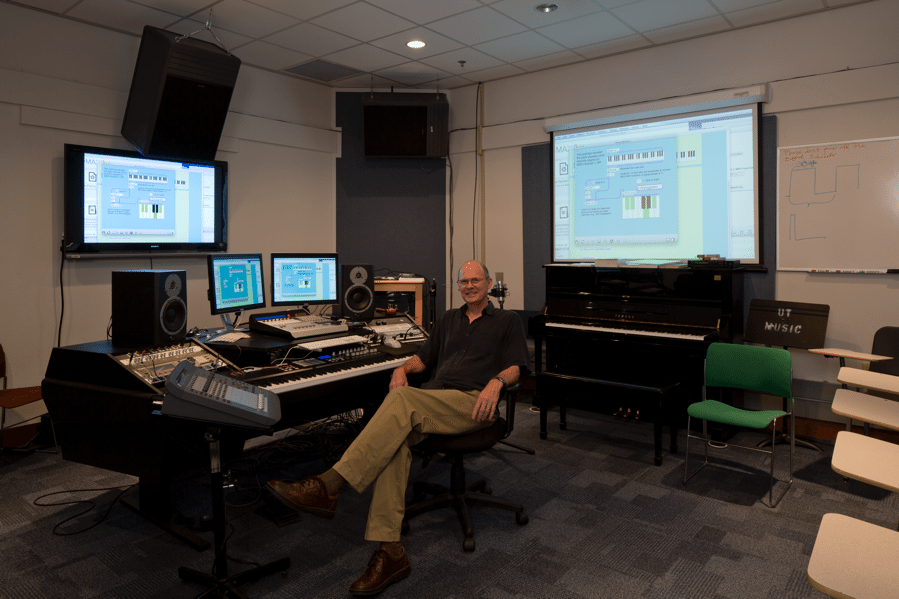

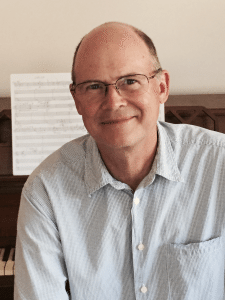

I consider myself very fortunate to have studied electroacoustic music with Russell Pinkston while pursuing a doctorate at The University of Texas from 2010 to 2015. Russell is a founding member of SEAMUS, and served as the organization’s president from 2004 to 2007. A gifted and humble teacher, he was an invaluable mentor in many respects while I was as student at UT Austin. Conducting this interview was an enjoyable way to revisit some topics which perpetually underscored my electroacoustic education, but were, perhaps, not always explicitly discussed.

How do you define electro-acoustic music, and how do you approach composing it?

First, let me say that I’m philosophically opposed to the whole idea of categorizing music – especially new music – with any real exactitude. I recently came across a book entitled “It’s a Portrait If I Say So,” which according to its publisher is “an exploration of the rise and evolution of abstract, symbolic, and conceptual portraiture in American art.” The picture on the front cover is of a fingerprint, which is certainly a kind of portrait. But how liberating that idea is! A portrait doesn’t always have to be a picture or painting of a face! So in the interest of broadening our definition of EAM as much as possible (for the purpose of membership building, if nothing else), I’m tempted to answer, “it’s electroacoustic music if you say so!” But since we are members of the Society for Electro-Acoustic Music in the United States, I suppose we have to define what we mean by that from time to time. And I’m personally content with the definition on our website: “Electro-Acoustic music is a term used to describe those musics which are dependent on electronic technology for their creation and/or performance.” That lets us include the Illiac Suite, Silver Apples of the Moon, Variations pour une Porte et un Soupir, and Switched on Bach.

As for how I personally approach composing electroacoustic music, it depends on what part of the compositional process we are talking about. When composing an electroacoustic piece, my first steps are devoted to creating the palette of sounds, whereas that is usually a given when writing acoustic music. But with respect to the generation and development of musical ideas – building narrative, structure, form, pacing, et cetera, I can honestly say that it is no different from how I approach composing an acoustic piece. I come up with some ideas I like, usually through improvisation; I analyze them, experiment with them, and try to uncover all their possible implications. For me, composing is a continual process of questioning and discovery. What do I like about a particular sound or musical idea? What really defines it? What is essential to it (i.e., what can I remove from it without making it unrecognizable)? What is its antithesis? What could become of it? Where does it need to go and how long should it take to get there? These questions apply as much to a theme, or motive, or collection of pitches, as they do to the spectromorphology of an abstract sound. The techniques used to transform and develop the materials may be different, but not the essential nature of the process. I am not a systems guy, or a maker of diagrams and/or pre-compositional maps, by the way. My approach is closer to that of the author, Stephen King, who has said that he never knows what’s going to happen to the characters in his books. It seems to me that if your characters are interesting enough, they will gradually reveal more and more about themselves to you as you work with them. Eventually, their story will begin to write itself, and it will be better for not having been forced into a pre-compositional mold.

What drives your philosophical opposition to categorizing new music? Have you always felt this way, or have your feelings shifted over the years?

What drives your philosophical opposition to categorizing new music? Have you always felt this way, or have your feelings shifted over the years?

I have no problem with categorizing old music. Indeed, it helps us make sense of historically important trends and to understand how they may have influenced the work of various composers. But I do have a problem with putting contemporary music into “boxes,” because I think it tends to stifle creativity and encourages a kind of laziness on the part of critics and theorists. It can stifle creativity if a young composer decides s/he needs to fit into a particular box in order to be successful, professionally, or to gain the respect and approval of certain colleagues and mentors. It can encourage critical laziness, in that it is always easier to evaluate a piece based on the extent to which it fits (or doesn’t fit) into a particular category, than it is to really analyze the music and evaluate it on its own terms. And especially when it comes to defining “electroacoustic music,” in terms of what it is and what it isn’t, I am concerned about the negative effects of discrimination based on personal aesthetic biases. As an organization, I believe that SEAMUS should be as inclusive as possible, and hence, that we should avoid defining ourselves (and our music) too specifically. I am proud of the fact that we admit performers and inventors, as well as composers, to join SEAMUS, and that we once gave the SEAMUS Award to Les Paul. But in addition, all my career in academia, I have fought against what Sam Adler once called “the ghettoization of electronic music” – something that has been all too common, particularly in conservatories. How often have we heard (or heard it implied) that electronic music is not “real” music, or that composers who specialize in it are not “real composers?” Or simply that someone “doesn’t like electronic music,” period? We first have to respond to this kind of thing by asking, “how do you define electronic music?” And then, “how much of it have you heard?” Usually, of course, the people who express such categorically negative views of “electronic music” have defined it for themselves, based on very limited knowledge. Moreover, since they already have a negative opinion, they tend to remain willfully ignorant of it. As the author, Eve Zibart, has said, “prejudice rarely survives experience.” I agree, but I would add that the problem begins by trying to make everything (people, music, whatever) fit neatly into boxes, big or small.

Has your philosophy or approach to composing EA music changed over the years? If so, how and why?

Well, if I have a “philosophy,” it is that composing EA music is fundamentally no different from composing acoustic music, as I already mentioned. We may work with some different materials, but we are still organizing sounds in time, we still need to construct some kind of narrative, we still need to be concerned with pacing, timing, form, motivic development, texture, timbre, “orchestration,” etc. And that philosophy has not changed over the years. But my approach to composing EA music has definitely changed – several times, in fact. Some of this has to do with the constantly changing technology, of course. I don’t splice tape or punch computer cards any more. But other important factors are my personal growth, as a composer, and the types of pieces I have composed at different times in my career. Perhaps because I was a song writer before I was a “composer,” my initial approach to writing EA music was almost exclusively focused on pitch and rhythm. I was interested in finding cool sounds on the synthesizer, but I tended to use them more or less in the same way I used acoustic instruments. And my teachers (Appleton, Arel, Davidovsky, and Charles Dodge) were also pretty pitch-oriented, so that probably reinforced this approach. It was only after discovering the music of some contemporary acousmatic composers (Gobeil, Normandeau, Harrison, etc), that I began using more concrète materials and giving more weight to the sounds, themselves. At about this time, I was also writing a lot of music for a local modern dance company, and that music needed to be more abstract, and also flexible, with respect to timing. So I went through a period in which my approach was first to look for interesting natural sounds, and then begin manipulating and transforming them in various ways, to build a palette of sounds to use in my composition. I still was interested in pitch and rhythm, but I also began focusing more on texture, gesture, and timbre. More recently, I have been composing a lot of interactive pieces for solo instruments (Gerrymander, Lizamander, Zylamander, etc), and that has necessitated a return to a more traditional approach. I still start by searching for interesting sounds – often from extended techniques produced by the instrument(s) for which I am writing. But my primary focus in these works is on what the performer will be playing, so I tend to organize the composition around those pitches and rhythms.

Are there any significant works or events that have noticeably shaped your development as a teacher or composer?

There are numerous works that have influenced me as a composer, of course – too many to count, really. But I would say that three of my own primary teachers – Jon Appleton, Jack Beeson, and Mario Davidovsky – had a big influence on my development as a teacher. Jon Appleton had this wonderfully enthusiastic way of teaching – full of joie de vivre. He could be critical at times, but he was very open-minded and always positive and encouraging. I’ll never forget his comment about my first piece of electronic music: “I think it’s super fantastic, Russ! Of course, you’re going to hate it someday!” And then he put it on an album with one of his own pieces and some other students’ work. Sure enough, I hate that piece now! But I learned from my experience with Jon how important it is to let young composers find their own way, not to force them into a particular mold, but to encourage their innate creative instincts, and above all, to “do no harm.” From both Jack and Mario, I learned the value of the small, informal, weekly seminar. We students would bring in our works-in-progress, and while we would always get some helpful comments and suggestions from our teachers, they would encourage a free and open discussion, which everyone participated in. The result was that we all learned as much from our fellow students as we did from our professors, and at least as important, we developed a real camaraderie. I still count my fellow students at Columbia as some of my closest friends in music.

In interacting with students over the years, have you noticed any significant or long-term trends? For example, in contrast with twenty years ago, the electronic music landscape is saturated with software/hardware tools, video tutorials, high-powered mobile computing devices, etc. Do you feel as if there have been tangible consequences on teaching and learning electronic music in academia?

These are important questions, because they touch on something fundamental and far reaching about the relationship between technology, educational strategies, ways of learning, and productivity – and not just in the field of electroacoustic music. There really has only been one significant “trend” during my career as an educator, which is the gradual replacement of analog with digital technology. And obviously, all of us who started with tape machines, analog synthesizers, and mainframe computers have had to gradually adapt our approach to teaching electronic and computer music, just as we have also had to continually update and modify our studios. But I think the more interesting question is the second one, relating to “tangible consequences.” When the first voltage controlled keyboards appeared, there were some who expressed concern that they would encourage composers to use the analog synthesizers in conventional ways – more like organs – and that having to record every sound in a piece individually, and then cutting the tape to the exact length necessary to articulate a particular rhythm, had the benefit of enforcing a certain discipline on your compositional process. I can personally attest to this! But having a keyboard doesn’t preclude having a disciplined approach to composition; it just makes some things a whole lot easier. With every advance in technology, new possibilities are opened, even as some things we may have valued highly may seem to be lost. And the new possibilities tend to allow composers to work at a higher level, which then introduces a whole new set of techniques and problems that we hadn’t had to deal with before, either as composers, or as teachers. There are valuable lessons to be learned from cutting and splicing tape, but do we really want to spend time teaching our students how to use an obsolete technology? We have to be willing to let some things that were a cherished part of our curriculum go, in favor of having the time in a semester to focus on the latest techniques that our students need to master. (I feel the same way about the music history sequence, by the way!) All that said, I still teach students in my computer music courses how to build the classic synthesis and processing algorithms from scratch, not only because it’s a great way to teach basic programming skills in any language, but also because it will help them master whatever commercial plugins and soft synths they own more quickly, and ultimately take better advantage of them. I have to say, though, that there will probably come a time when I feel I can no longer afford to do that.

On the topic of “the ghettoization of electronic music,” surely, this trend is part of the reason why SEAMUS and similar organizations came to exist— right? Broadly, what are your thoughts on the evolution of SEAMUS and electronic music? Do you feel like SEAMUS has been effective in accomplishing its goals?

Our Articles of Incorporation state that the “specific purpose of this corporation is to encourage the composition, dissemination and study of electroacoustic music.” I don’t think there is any question that SEAMUS has been effective in the first two areas, considering the ASCAP/SEAMUS award, the CD series, the annual conferences, the journal, newsletter, website, etc. But when it comes to encouraging the study of electroacoustic music, I think we could do more. The ghettoization of electronic music in academia is real, at least in most conservatories. It’s also evident in the relative rarity of articles about electroacoustic pieces in the mainstream music theory journals. Articles about electroacoustic music tend to appear in journals devoted specifically to the genre, just as pieces of electroacoustic music are most likely to be performed in concerts and festivals established expressly for that purpose. This was not always the case. The reasons for the current situation are complicated and multi-factored, and it is certainly true that some responsibility must lie with us electroacoustic composers. But the result is that there are numerous degree programs in electronic and computer music now, often completely separate from the composition programs. Indeed, one might argue that the whole field of Music Technology is a by-product of the gradual separation of electroacoustic music from traditional music composition programs. Inevitably, the curricular focus of these degrees is more and more on the technical/industrial, and less and less on the musical/aesthetical. Some will say this a good thing, but I don’t agree. I think it’s a big problem for our field. I’m not sure what SEAMUS can do to address it, as an organization, but I think it should be discussed.

What has been your most memorable SEAMUS conference?

I can’t say that there is any one conference that sticks out in my mind, unless it’s the one we held here at Texas back in 1993, for reasons obvious to anyone who has ever run one! But I do have some specific memories from various conferences that definitely stand out in my mind, most of which relate to the banquets where we honored the recipients of SEAMUS Award and SEAMUS/ASCAP Commission. It was very satisfying to be President at four of those occasions, and hence, to have the honor and pleasure of giving these awards on behalf of the organization. Actually, though, one of my most vivid SEAMUS memories is not of a conference, at all, but of the meeting at CalArts in 1984, where we founded the organization. I was fresh out of grad school, had just started teaching at Texas, and I didn’t know anyone there except Jon Appleton, who had invited me, so I mostly just kept quiet, watched, and listened. One of the things that stands out in my mind was the clear consensus about wanting SEAMUS to be focused primarily on music, in contrast to some other national and international organizations (the ICMC, in particular), whose focus seemed more and more to be on research and technology. Another point of emphasis was that we didn’t want to be just another organization devoted to academic music and university composers, but one that embraced popular idioms and freelance composers, as well. Both of these ideas really appealed to me at the time; they still do. One other memory of that meeting stands out to this day: Barry Schrader suggesting the name SEAMUS and pronouncing it “SeeMuse,” and Jon Appleton’s immediately countering with a laugh and saying, “no, we should call it Seamus, like the Irish name.” Barry did not concur, and as many longtime SEAMUS members know, this led to years of controversy over how to pronounce our name, which was finally settled by the SEAMUS Board, who decreed that the official pronunciation was like the Irish name. I think this was decided at the Members Meeting of some conference, by vote of those in attendance, but I’m not sure. (I hope I am not re-opening that can of worms here!)