SEAMUS member Eric Lyon explores the rich and diverse work and background of 2016 SEAMUS Award winner Pamela Z in the following interview, including her residency in Japan, her background as a singer/ songwriter and radio programmer, and much more.

“There’s a tension in my work between not having any particular desire to be political and wanting to play with language and human interaction and tendencies in ways that are bound to become political. I sort of slip on the banana peel of politics by just playing with language.”

—Pamela Z

EL: We first got to know each other in Japan during the 1990s so that seems like a good place and time to start. Living in Japan affected me profoundly – culturally, philosophically, artistically, and personally. Your residency in Japan culminated in the work Gaijin in which you explore the notion of foreignness. I would love to learn more about how you evolved, and what lessons you learned from your time in Japan.

PZ: Japan was very interesting for me. I was actually drawn to Japanese language, and attracted to a kind of minimalist Japanese visual aesthetic for many years before ever visiting Japan. I had taken Japanese language classes and studied the phonetic alphabet and diction at a time when I had no concrete plan for actually going there. I used to go around pronouncing the katatana on the packaging of things from Japan (like the 12-inch imports at Tower Records, where I worked in the mid-late ‘80s) – reading out loud things like “De-bi-ddo Bo-u-i-i”, “Mi-kku Ji-a-ga-a”, “Ku-ra-fu-to-wa-a-ku” and “Je-i-ro Bi-a-fu-ra”. My co-workers there were duly amused and would test me by covering up the “Romaji” and asking me to read the names. So, I was naturally delighted when I got invited (in 1996) to do a tour in Japan – performing in a Festival called Interlink, and again, when I received a Japan/US Friendship Commission fellowship to do a 6-month residency there in 1999. That was when I met you. We must have been both attending some kind of electronic music or sound art event – perhaps at ICC? Anyhow, my six months in Japan had a pretty strong effect on me. One of my most profound lessons was finding out what it is like to truly be an alien in the place where you are living. There was something very intense about being the foreigner – the “gaijin.” It was also my most immersive language-learning experience – being the first time I ever stayed so long in a place where English was not the primary language. Although I didn’t approach fluency by any means, I absorbed a lot of Japanese language while there and, by the time I left, I could hold my own with small talk or ordering meals in restaurants, and I had memorized somewhere in the neighborhood of 250 kanji. (Nowhere near the 1800 required to even read a newspaper, but still…) And, while there, I did study with the butoh master Kazuo Ohno, and his son Yoshito in Yokohama – an experience that greatly impacted my relationship to movement. Like you said, when I returned home to San Francisco, I was inspired to create a full evening, multi-media performance work called Gaijin, which included my own voice & electronics, multi-channel video projections, and the live work of three Butoh dancers.

EL: “Je-i-ro Bi-a-fu-ra” is totally priceless! I was a big fan of the Dead Kennedys during the 1980s. While we’re on the subject of pop music, before becoming “Pamela Z” you were a successful singer-songwriter. I’m fascinated by your decision to transition from pop musician to computer music composer/performer. There’s a clear thread in that you retained your voice as a primary expressive instrument. And in the end you became a very successful computer musician as well. But surely, that must have seemed like a risky move at the time. Could you please tell us about your early singer-songwriter career, and why you chose to transition to computer music?

PZ: By the late 1970s, although I had a degree in music and had studied bel canto voice, I was making my living as a singer/songwriter – busking and playing folk and rock music in clubs for a living. My main influences were artists like Joni Mitchell, Laura Nyro, and icons of British invasion rock. I was also volunteering as a radio programmer at KGNU, Boulder’s public radio station – doing a free-form music program called “The Tuesday Afternoon Sound Alternative.”

On that weekly, 3-hour show, I took pride in the fact that I would freely traverse territory ranging from Varése, Stockhausen, and Philip Glass to the Ramones the Residents, and Laurie Anderson – sometimes all within the same half hour of segment. Largely through doing this radio program, I became more and more familiar with and engaged by contemporary classical music, experimental music, electroacoustic music, sound art, and text-sound poetry. By the early 1980s, I started feeling dissatisfied with the fact that the music I was performing was completely different from the music I was listening to. I had become much more interested in experimental music than I was in folk-rock, and was hungrily trying to expand or transform my work to reflect that.

I started playing with processing my voice electronically (mainly using digital delays and multi-effects processors) to compose layered pieces. In fact, the most profound shift I’ve ever experienced in my work occurred when I acquired my first processor (around 1982). I bought an Ibanez DM1000 Digital Delay, and the very moment I started processing my voice, I embarked on an entirely different path in composing and performing music.

I was able to make layers of sound in real time and create fairly complex and dense pieces with just my live voice as the sound source. Very quickly my entire compositional style transformed, and I began listening to sound in a different way. I became fascinated with repetition and keenly aware of the changes in our perception of small fragments of sound when we hear them repeated at length. I started composing works based on the melodic and rhythmic attributes of human speech, and I began to focus a lot more on timbre, texture, and layering. These elements started to equal and even surpass my previous emphasis on melody and harmony.

I eventually bought more delay units with more memory – allowing me to create longer and more varied loops. Combining the sound of that stack of delays lead to my innocent discovery of out-of-phase loops (I was completely unaware of Reich’s early works at that point), and the polyrhythmic/arrhythmic sound of those loops became an important hallmark of my work.

My shift to involving a computer wasn’t until more than 15 years later (around 1999) when Max had added MSP (Max Signal Processing) – making it possible for me to begin porting all the work I’d done with rack-mountable effects processors into Max/MSP patches.

EL: That’s a fascinating trajectory! Radio stations are wonderful and inspiring places. I was a DJ at WPRB in Princeton, where I started a new music show called Arcana. I was constantly learning about weirder, more remote areas of recorded music from my fellow DJs, whose musical interests were all over the map. The freeform format of your programming is noteworthy because there was such strong pressure to keep radio programming within genre boundaries during the 1980s. These days, outlets like YouTube and SoundCloud, along with internet stations like WFMU have made freeform a much more accessible format. Do you feel that the world has caught up with you in some ways? That things you were doing back in the 1980s and 1990s that might have seemed kind of fringe or cult have taken off in a bigger way recently? If so, how has that affected how you think about your current creative directions?

PZ: That’s an interesting question. I do feel as though the world at large has come to embrace the juxtaposition of varied work more and more over time. And, our current modes of transmission must have a lot to do with that. And, I think it’s a little bit of a mixed blessing.

The way I remember it, there was a time when people held much more tightly to genre boundaries. And, people’s listening experiences were often limited by rigidly programmed radio stations, and the bounds of their own music collections. Although I kind of remember – especially on the more popular music side – that things were actually more mixed and free, way back in the 60s or so, when singles (in the form of vinyl 45rpm records) were a thing. After that, music listening became more album-oriented, and tracks also became longer. Radio programming became more homogenous, and people’s exposure became more tightly confined by genre.

Then, along came multi-CD players that could be programmed on shuffle, followed by digital music players that could shuffle one’s entire music collection. Then, once the internet became a viable means for streaming music, people gained the ability to shuffle everyone’s music collection. Through all of this, people gained broader, more varied exposure to works from many genres. Also, the inevitable seepage from the experimental world to the mainstream world exponentially sped up.

So, in some ways, this is really great because, in theory, wider circles of people are being exposed to wider ranges of genres, and to rampant boundary-breaking. On the other hand, it seems a pity to me, at times, that everything is being reduced to the concept of a “song.” And that people are perhaps listening with more limited attention spans and no longer drinking in the beauty of a carefully designed sequence of pieces – much less the majesty of powerful, full album-length works.

So, in some ways, these trends just make me want to compose larger-scale, more full-length works. But, alas, my approach to doing that always seems to be kind of modular in nature – with a series of short song-length sections or movements strung together to make the whole. Chances are, those sections are bound to be separated from one another and destined to pepper someone’s iTunes shuffle, YouTube playlist, or Spotify channel…

EL: I’ve been to many of your performances, for a variety of audiences, and I’ve noticed that you always generate a wonderful rapport with the audience. That is not always the case for live electronic music, which can be off-putting to general audiences. Could you tell us how you think about, and cultivate your relationships with your audiences?

PZ: Although my audiences are primarily made up of people who are already interested in contemporary or experimental music, I think that my use of voice and the body go a long way in lending a kind of accessibility to the work. The sound of the human voice does tend to have a powerful effect on humans. I also think that the varied nature of my interests, influences, and artistic leanings really contributes to my audience connection. The fact that my work and my interests extend into the visual art world broadens my audience to include visual art enthusiasts. And, because a lot of my work plays with language, I connect with audiences interested in poetry, experimental theater, and performance art. I think there is a public that is attracted to interdisciplinary and cross-disciplinary work.

Part of my strength as an artist happens to lie in physically relating to the audience in a performative way. I put a certain amount of my focus there, because that happens to be an essential component of my art. I don’t subscribe to the notion that this is a superior approach to art-making. I’m just as engaged by composers whose strengths lie entirely in the creation of astoundingly beautiful sonic works. And, I don’t see any value in expecting those people to water down their efforts by trying to also be strong physical performers. For some people, 100% of their on-stage work is funneled (rightfully) into the creation and presentation of brilliant music that could just as well be performed in total darkness. Each artist needs to work in a way that suits their own particular strengths and predilections, and that places the focus on what is essential to the work itself.

EL: You talk about your work as a performer, but you’re also an accomplished composer. Could you talk about your compositional work when you’re not front-and-center as a performer?

PZ: For many years, I composed almost exclusively for my own voice and electronics. Although there were a few exceptions early in my career when I made theatrical performance work involving additional players, for the most part, I didn’t really begin to write for other people until I started getting chamber music commissions. I think the first significant one was for the Bang on a Can All-Stars with their “People’s Commissioning Fund” in 1998.

I composed a piece for them called The Schmetterling, and it was quite a feat for me because it was the first time I ever had to produce a proper score and generate parts. At the time I didn’t have Sibelius1. I’m not sure if Sibelius even existed in 1998? I think I was probably using Finale2, and I was terrible at Finale, so I think I hired a Mills student as a copyist to make it legible and generate the parts. But I did do some funny things like inserting graphics. I had a sort of elongated butterfly form that would appear right in the staff instead of notes for certain parts of it, but for the most part it was just conventional musical notation

Since then I’ve gotten commissions from the Left Coast Chamber Ensemble, from Ethel3, and I did something for the San Francisco Contemporary Music Players – a duet with Steve Schick’s percussion and my voice and electronics. One of my most recent commissions was a work for Kronos Quartet called And the Movement of the Tongue, and I was really pleased with the outcome of that piece.

With the Kronos piece, I focused on speaking accents – specifically accented English. I must have interviewed upwards of 30 people with different accents – regional American accents and the accents of people who speak English as a second language. Then I cut them up into little fragments of speech and built a series of text collages that became a kind of armature for the string parts that I wrote for them.

A lot of the melodies in those string parts were derived from the melodic material that’s found in the human speaking voice – the actual pitch material that comes from the frequency of the syllables that are spoken.

EL: That idea of deriving melodies from the melodic shape of speech immediately puts me in the mind of certain techniques that Steve Reich developed early on. I’m thinking of his piece Come Out, which is less well-known than It’s Going to Rain, but which also derives very diatonic melodic patterns from recorded voice. And then more recently would be Different Trains. So do you draw any connection between that practice with Reich’s work and your work, or is it completely separate?

PZ: I think contemporary music people who work with electronics have a long history of finding melody in speech and making it part of their composition – maybe starting with Steve Reich or maybe even before him. It’s hard for me to gauge how much of that was influence from hearing the work of others who have done it and how much of it was because of the real reason I think we all probably do this–which is the advent of the new tools we now use. Once we had access to tape recorders and could splice together loops and repeat things, we all discovered the melody that exists in speech. People think of speech as being un-pitched. But, in fact, all sound is pitched, because pitch is just frequency and every sound has frequency.

When you’re not thinking about pitch, for example when you’re talking and not singing, you never sit on any particular pitch for any length of time and you don’t ever precisely repeat what you doing. So the patterns aren’t heard and the pitches go un-noticed. But the minute you open up a digital delay line and start looping a very short passage of speech, it only takes two or three repeats before you become aware that there’s a little song in there! I think this discovery is made independently by every person who’s ever recorded and looped a bit of speech. The sudden shock of hearing a melody! And I think it’s kind of a symptom of the tools that we now have access to – starting with tape loops and then digital samples.

As a musician it’s very hard not to latch onto that little bit of melodic material and hear the music in it. And there are quite a few melodies throughout my Kronos piece that completely emerge from repeating figures of speech fragments. There are even rich harmonies that develop. When I interview the people, there are always one or two questions to which everyone says the same thing. So I end up with this beautiful library of thirty different people saying the same words, which I then stack on top of each other to get amazing and bizarre choral sounds – like some kind of Greek chorus. And it’s really very exciting to me. I never tire of the sound of that, so it shows up in a lot of my pieces.

EL: Because text is such an important part of your work and a lot of your work is dramatically inclined in various ways – I’m thinking of pieces like Gaijin and maybe Baggage Allowance – I think it’s very easy to situate those pieces in a political context. So, how do you think about the politics of some of the work you’re doing? And what sort of critical responses have you gotten that may have been reactions to those critics’ perception of the political aspects of your work.

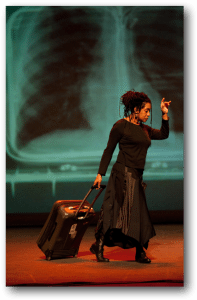

Photo: Valerie Oliveiro

PZ: I never deliberately set out to make work that is political in nature. As a matter fact, there’s a part of me that really loves abstractness in work, and I have an envy of making work that is completely abstract. But I know that I have tendencies toward wanting to play with language and, as soon as you introduce language that has a discernible meaning to the listener, it’s impossible to avoid that meaning becoming at least one of the layers of the work. So I’m aware of that, and I don’t try to pretend otherwise. But, even though I make work that is “about” certain things, I have to confess that the subject matter I choose is often just something to hang the work on, and I always approach the subject matter in as open-ended a way as possible. I tend to choose kind of broad, open-ended ideas that can be approached from lots of different angles. In one of my earliest large-scale works, Parts of Speech, I explored language from many different angles, ranging from just the sound of the language to a certain amusement with grammatical structure. I had a whole section just making sentences that were grammatically correct but actually had no meaning. And, I had a section about the language of asking. I was just reading from those funding pleas that come in the mail from charities and foundations. And I was juxtaposing that kind of asking with the voices of homeless people or panhandlers asking for money. So, although I didn’t do that to be political, the minute you juxtapose endowed major foundations asking wealthy donors for money with the voices of people asking for a handful of change so they can get something to eat, right away something political is injected into it. By just putting those things side-by-side it becomes political.

There was another section in that piece exploring the kinds of things a woman hears from guys when she walks down the street alone. I made a bank of samples of things like “Hey baby can I walk with you?”, “You sure look good!” etcetera, and then I was triggering them with the BodySynth™ gesture controller. So I’m using my body to trigger the sounds of men on the street saying things about my body.

So, I can’t in good conscience say that I don’t make political work, but I can be perfectly honest in saying that I never approach my work with the idea of trying to be political. There’s a tension in my work between not having any particular desire to be political and wanting to play with language and human interaction and tendencies in ways that are bound to become political. I sort of slip on the banana peel of politics by just playing with language.

EL: So I’d like to ask about your take on identity politics. Of course I think of you as a sound artist and a dear friend, but other observers might pay more attention to the aspect of your identity as a woman of color. How has this affected the way some people take in and react to your work? And are these or other aspects of identity important to you?

PZ: One thing I regularly encounter is the way that communities like to claim their people. Somebody put up a Wikipedia article on me years ago, and I was curious to see how people would edit it over time. At some point, inevitably, somebody edited it to make sure that it was stated upfront in the article that I’m African-American. So literally at the very beginning of the article it said something like “Pamela Z, the African American composer….” And I thought “OK, I totally get it.” It is true that people of color are very under-represented in the experimental music and arts world. So I guess it was important to them, when they saw a Wikipedia article on one, to let people know that she’s not only a composer/performer doing experimental work, but she’s an African-American composer/performer doing experimental work.

The thing is, I’ve always been one of those people whose sense of identity does not fall within the expected parameters. People are presumed to focus their sense of identity, community, and culture around their racial or national background and their cultural heritage – and maybe their gender, gender identity, and their sexual orientation. But, if I were to claim a group that I think of as “my people,” it would be artists who work experimentally and the people who love that kind of work. Those are the things I actively seek out, and those are the people I want to be around. If some of those people happen to have the same gender or racial background as me, that’s nice too. But the people who feel like community to me are those who are interested in the things that interest me.

I think one of the most difficult things about not investing one’s identity in the attributes that most people are expecting is the knowledge that people see your work through a particular lens. And, no matter what you do, even the most well-meaning people often view your work through a kind of lens that makes them evaluate or appreciate it differently. Reviewers often write things like, “Pamela Z combines high technology with street-smarts and soulful singing.” And I think, “Do I? I didn’t think I did that. Street-smarts?”

EL: I believe that’s what they call confirmation bias.

PZ: And this would be in a totally positive review by somebody who was trying to say how great they thought I was. But the language they’re using to describe me contains words I’m quite certain would not be used to describe another artist (who’s not black) doing things with voice and electronics. Like, I don’t think I’ve ever read an article about Amy X Neuburg that mentioned “street-smarts” or “soulful singing.”

And, often people will insert “jazz” as a descriptor. This is also a big pet peeve of George Lewis’. George doesn’t consider himself to be a jazz musician. But, because he’s black, plays trombone, and employs improvisation, he can’t escape being constantly classified as jazz. And it’s even more baffling to me when people refer to my work as jazz. I’m almost anti-jazz, you know. And I don’t mean that in the way of being against jazz but, stylistically, I generally make work that couldn’t be further from jazz. If you comb through everything I’ve done, there may be one or two pieces I have with some kind of jazzy element as part of the texture, but that’s the exception to the rule.

EL: Looking ahead, what do you most hope to achieve artistically in the next 10 years?

PZ: I’ve been using gesture controllers to play sampled sounds and manipulate some of my processing for years, but lately I’ve really had a desire to better integrate the performative qualities of my work. Especially for theatrical works, I’d like to able to physically distance myself from the computer entirely and manipulate more of the electronics with gesture control.

I’m very inspired by artists like Robert Wilson, who make beautiful works that involve the power of the visual image on stage. I really want to be able to – without attenuating what I’m doing sonically – make works that allow me to be very present in a theatrical way on the stage while still managing to manipulate my gear without having my nose in the laptop at all. So that’s one of the things I’m always working towards. In a simple concert that isn’t a theatrical production, I have nothing against standing there and manipulating the computer very actively and obviously. I don’t mind doing that at all. But I like to have the option to free myself from that at times when it makes sense. I’ve made a lot of progress in that direction over the years, but I’m actively working on further augmenting that aspect of my work.

Also, I’ve really enjoyed recent opportunities to compose for other performers. I would love to make more works for groups – perhaps a big choral work for a professional choir or an orchestral work. I’d also love to make an opera involving other performers beside myself. I’ve made so many solo performance works, so I would really enjoy working with other bodies and voices on the stage.

I’d also like to do make more sound and video installations, and I want to develop more interactive video performance work. I want to take the time to get myself more up-to-speed with the software I use for live video, so that I can find more interesting ways of playing with the body and image and the interaction between the two. Those are just a few of the goals I’m working towards.

Photo: Goran Vejvoda

EL: Well that seems like a wonderful place to end. This was too much fun!

PZ: Very lovely talking to you, Eric!

_________________________________________________

1 Music notation software (now distributed by AVID).

2 Music notation software (developed by MakeMusic).

3 New York-based string quartet.