“The human being knows himself only insofar as he knows the world; he perceives the world only in himself, and himself only in the world. Every new object, clearly seen, opens up a new organ of perception in us.”

—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Kim Cascone responds to questions posed by newsletter editor Steve Ricks and talks about his background, the creative process, meditation, and his current projects.

SR: You mention recognizing at an early age the “power to manipulate sounds with tape recorders – and later on with synthesizers and computers.” In your essay “Transcendigital Imagination: Developing Organs of Subtle Perception” you have some concerns about this relationship—thinking of the sound as the “other” or an outside object. When did your perception change?

KC: My perception began to change after learning to meditate at a Buddhist meditation center in the 70’s. I noticed a subtle shift mainly in my perception of sound events. Sound shifted from being a sensory to a supersensory experience. This happened while I was in music school so the changes were more noticeable because I was immersed in a sonically rich environment. I began to sense the “essence” or “psychic signature” that leaked through sounds which I sensed as “soundshapes.” Instead of sound being a sensory event which happened to me I found that sound acted more as a conduit or a portal.

Frits Julius, a student of Rudolf Steiner, wrote a wonderful little book titled “Sound Between Matter and Spirit.” In it Julius suggests that the color of a blue flower is not really part of the flower itself, but emanates from another place through the form of the flower and that one’s imagination could travel into the blueness of the form into another realm.

I began to sense sound in a similar way, i.e., the “event” of a sound acted as a portal through which its essence or “signature” emanated but also through which the imagination could travel. I can only compare it to the feeling of hypnagogia, that feeling one has as they are just about to fall asleep when strange visions or thoughts occur.

I began to sense sound in a similar way, i.e., the “event” of a sound acted as a portal through which its essence or “signature” emanated but also through which the imagination could travel. I can only compare it to the feeling of hypnagogia, that feeling one has as they are just about to fall asleep when strange visions or thoughts occur.

I use an exercise in my Subtle Listening workshops in which I ask students to sense the “shape” of a word. From there they begin to sense the size, shape, weight, color, texture of sounds heard in their environments and draw them on paper. This exercise gets them used to visualizing sound as well as teaches them how to get what’s in their imagination into a physical manifestation. You can see this same process at work in many graphically notated scores.

I have yet to teach the more advanced forms of “traveling through a sound event” because one needs to have developed new organs of perception first. I need more work with this meditation as well since it is an advanced and difficult practice.

SR: How would an artist in a “heightened state of imaginative awareness” behave differently in practice? I assume it could be different for every person, but I assume you are talking not just about a different state of being but actually different behavior in the physical world? So it’s not just about responding differently to sounds which already exist or are already recorded, but that the act/process/tools/etc. of recording/creating would change?

KC: You are correct in that it is different for each person but I don’t distinguish a state of being from behavior in the physical world. They blend into one and the same thing. One’s consciousness creates the world and our observations affect it. But even that dichotomy can be collapsed into something called consciousness…everything is consciousness although we separate it according to our five senses.

The Sufi musician/philosopher Hazrat Inayat Khan wrote that although humans have five senses with which we distinguish the world there is really only one sense…all that is visible and all that is audible is one and the same.

As creatives we can choose to be limited by our physical senses or tap into the supersensory as artists and philosophers have been doing for thousands of years. I feel that artists need to relearn this skill to achieve a balance with our current techno-materialist consciousness or we can continue our slide into a devastating future.

The philosopher Jean Gebser called this consciousness Integral Structure because it integrates intuitive/spiritual and materialist modes of consciousness.

Once an artist develops new “organs of perception” they can develop their own way of manifesting the supersensory. There are artists who achieve this state without consciously knowing it. Poets and mystics are able to sense and express the supersensory, while many of today’s sound artists are only able to let the tool express itself. Technology presents a “use-narrative”, i.e., workflow, that determines the content created with it. This is what I’m trying to correct in my Subtle Listening workshops.

SR: How long do you meditate each day? How long in one “session” is required for you to get the experience you need? Is meditation a creative act? What are you composing/creating?

KC: My meditation practice is influenced by techniques I’ve collected and modified over the past 40 years. I meditate for 30 to 45 minutes every day – sometimes I take advantage of the time I have on airplanes and meditate then.

The act of meditation is no more a creative act than eating dinner or washing your hands. Meditation is a nutritive act that opens up ways of perceiving the “outer” world as a continuum with your inner world or imagination. Any conscious intention (i.e., results, goals, etc.) held in the mind during meditation takes you out of the process. That being said, the creative act can be a type of meditation.

It’s best to let go of intentions, expectations or any other ego-related desires to establish a connection with ones unconscious. This is a common mistake that new meditators make. It is difficult for beginners to stop the “monkey mind” when they have intentions. Often times new meditators are worried they aren’t doing it correctly or don’t feel bliss or get results they are seeking or whatever. Once you stop holding onto intentions during meditation and let go you are then able to let the process happen all by itself. Meditation is a process, not an achievement.

SR: I often share the following quote from Luciano Berio with my students:

“Composers who work with new means in electronic music (computers included) tend to place their pasts in parentheses . . . Sometimes, one has the impression that they let themselves be chosen by the new technologies without being able to establish, dialectically, a real rapport and a true need for them. We can in fact pass indifferently from one system to another, from one computer to another—they are ever faster, more sophisticated, more powerful, and ever smaller—without really using musically that which was there.”

I think your critique of technology and how composers use it has similarities to Berio’s but is also distinct–how would you respond to Berio’s thoughts?

KC: One problem with technology is that, despite what people may claim, it is rarely transparent. Often times I hear people dismiss my statement: “the medium is no longer the message, the tool has become the message” because they are unable to see how commercial, off-the-shelf tools have an “agenda” embedded into the product. By agenda I mean a feature which collapses the steps of a complex process into a devastatingly simple red knob. The term used today is “workflow.”

By hiding the complexity involved in creating something and wiring the parameters to a single red knob the designers have already made creative decisions for the user and these decisions often steer the creative process towards a particular end. The problem is that if everyone is using the same simple red knob you are going to get clustering of stylistic results. Offloading complexity to a computer is good for hands-free smartphones while driving a car but I’m not sure it has done much good for culture.

Because off-the-shelf tools often over-determine creative artifacts I tell sound artists to learn to build their own tools in Pure Data or Max/MSP and to do pre-compositional work before opening a laptop. These programming environments allow an artist to solve their own aesthetic problems and let the project determine the technology used instead of the other way around.

That being said, a different sort of problem arises when people get caught up in the techo-materialism of programming and lose sight of the intuitive…what is most needed is balance of head, heart and hands.

SR: I recently interviewed composer Scott Johnson (who I found out meditates daily, fyi), and he is heavily influenced by evolutionary biology. He often referenced the idea that “the hand shapes itself to fit the tool” to describe his own process in using technology. What are your thoughts about this sentiment? It seems that what you’re calling for with “new organs of perception” is sort of the opposite to this way of thinking.

KC: To my way of thinking the tool should shape itself to fit the project. Ideally, a tool should be in a fluid state of “becoming” as you work with it. If your hand is shaping to fit the tool then the tool is too involved in determining the result via its agenda.

If a painter selects a particular type of brush that gives her a striated, thick brushstroke on canvas that is one thing, but music technology is an entire environment in itself — it is brush, paint, canvas and gallery all rolled into one. And it is difficult to disentangle these functions in today’s technology due to convergence.

The collapse of these functions into a single package has created an expectation of convenience, ease-of-use and real-time usage. People no longer have to carry a camera, a GPS, a laptop and a cell phone — all they need now is a single smartphone that fits in their pocket and provides a number of functions in one package…a single red knob as it were. So we have come to expect a similar collapse of functions in other things too because we want our technology to be convenient and easy to use.

But if all this complexity is hidden from view in music technology there is little opportunity to develop a deep understanding of the tool. The user doesn’t take responsiblity for the process. What your hand is “shaping to” is a predetermined agenda, ease-of-use, as implemented by a marketing department.

If you listen to Sufi music you can hear that the musicians are channeling something deeper than mere technical proficiency…they are conduits and like the color of the blue flower I mentioned earlier, the sounds made by their instruments act as portals through which the listener can travel.

SR: I’m interested in your statement that “a tool should be in a fluid state of ‘becoming’ as you work with it.” I’m interested in thinking about what is meant, or could be meant by “tool,” and also how what you’re talking about relates to composition for acoustic instruments, or voice, or whatever. If I am writing a piece for solo violin, what is the “tool” I am using . . . my technique, imagination, etc.? Or if I am creating a work that uses traditional instruments with electronics, or voice with electronics, or if I am giving particular concern to the space in which a piece or concert is presented–in what sense are these other elements the “tool” or part of the tool? In all of those situations, what would it mean for the tool to be in a fluid state of becoming?

KC: My definition of a tool is “one or more things that allow a thought to manifest from ones imagination into the world as an object.” We have different types of tools: cognitive tools, mental models, music notation, the violin itself, even the acoustics of a space — but they all form an assembly line consisting of functions that aid in the act of creation.

I tend to conflate all of these under the single term of “tool,” but people tend to reduce them to separate moving parts with different functions, while this is useful for solving problems or developing ideas it can limit how one views the act of creation.

If you view the act of creation as a process of “becoming” then the tool should really recede into the background and impart more than its own signature to the work. All the separate tools should blur into one fluidic function: to be a sort of “silent channel.”

This fluidity presents itself as a way of co-evolving with the act of creation, a fluidic tool changes shape as it performs the tasks necessary to complete the finished work — from imagination to final performance or recording.

The fluidic process doesn’t actually create the artifact so much as reveal it. Like the sculptor who finds the statue in the block of marble or the documentary filmmaker sifting though hours of interviews hunting for the key narrative, it’s all there already. We only need to unveil the final work via the process of becoming. This process of becoming doesn’t differentiate between our internal and external reality. Those distinctions are no longer useful or necessary – they just get in the way. Once that barrier is broken the creative act can manifest ones imagination much more easily.

SR: Also, when writing for acoustic/traditional instruments/voices, composers often speak of “idiomatic” writing–taking into account the inherent properties of the instrument, some of which are fixed (say the pitch range of the piano), or the capabilities of performers, etc. Is it valid to discuss or consider “idiomatic” writing for the electronic medium, in its various forms?

KC: The properties you mention are located in the materiality of the physical instrument – they are the mechanical aspects of an instrument that determine what can be written and played.

This is the outer manifestation of the instrument. There is also the inner essence or “psychic signature” of an instrument. Roland Barthes refers to this quality as “grain,” i.e., a transcendental, ineffable quality that cannot be quantified or empirically analyzed but is intuitively sensed in a work of art.

This quality comes from a place that transcends the mechanical aspect of the instrument. The same can be said for electronic instruments, if one has developed organs of perception they will help one to connect with the essence of an instrument, allowing the machine to enunciate the imagination as it travels through the conduit into the artifact. Acoustic instruments invite a different sort of relationship due to a level of physical mastery needed to form that channel or conduit, whereas electronic instruments today offload physical, and mental, mastery to the developer.

That being said, there are pieces of electronic music such as David Tudor’s “Rainforest” or Pauline Oliveros’ “I of IV” which channel that grain through contact mics and tape machines without foregrounding the technology.

SR: You obviously are concerned with the way technological tools can have an undesired influence on the creative process and a work itself. Is there a danger that teachers and mentors, or even peers–including their works–can have too much influence on an artist’s work, and if so, how have you dealt with this and what are your feelings about it?

KC: A friend of mine who teaches electronic music in a university says he feels like a vocational teacher rather than an art teacher. He feels there is too much emphasis on teaching the mechanics of production and says he ends up “teaching the manual” rather than nurturing the artistic process. Very little of the history of electronic music makes an impression on the students, it seems antiquated and boring because it doesn’t have a drum machine or fit into some micro-niche of EDM (electronic dance music). So in my experience there is less influence from teachers as opposed to the pop music marketplace which has taken on the role of mentor.

KC: A friend of mine who teaches electronic music in a university says he feels like a vocational teacher rather than an art teacher. He feels there is too much emphasis on teaching the mechanics of production and says he ends up “teaching the manual” rather than nurturing the artistic process. Very little of the history of electronic music makes an impression on the students, it seems antiquated and boring because it doesn’t have a drum machine or fit into some micro-niche of EDM (electronic dance music). So in my experience there is less influence from teachers as opposed to the pop music marketplace which has taken on the role of mentor.

SR: Are you still involved in .microsound.org? I really appreciated discovering it several years ago, and as an “academic” composer teaching at a somewhat isolated university, I appreciated how I felt that it connected me to this worldwide network of electronic music enthusiasts that were largely outside the academy and were open to discussing questions on a wide range of topics, from gear to aesthetic issues to whatever. Is it just my impression, or has the conversation died down a bit over the last few years? I never participated in any of the projects, like the one you proposed when DFW died, or the Pi Day projects–it seems it’s been a while since one of those happened. Is this just the natural course of things? What’s changed?

KC: I co-founded .microsound.org in 1999 before the Internet was turned into a medium for consumer data collection. At that time email and forums were the two most common ways to build a community on the Internet. Now there are any number of technologies, such as Facebook or Google Hangouts, with which to build a community. Over time many of the original members of the .microsound list have drifted onto other projects or lifestyles while others have migrated to the Facebook .microsound page. I’ve also moved on to concentrate on other things so there has been less involvement on my part.

Another reason for migration away from the list was that places like Soundcloud became centers for more visible distribution. Soundcloud has a prominent social component that email lists don’t. Lists feel too anachronistic to many newcomers these days. There is still a core constituency on the .microsound mailing list but it has quieted down a lot in the past 5 years or so.

As for .microsound projects, it became increasingly difficult to get people to contribute to them. I have theories as to why this is but I will save that for another time.

SR: How would you assess the work of “composers,” or even sound artists–again, probably the category most of the members of SEAMUS would fall into–in relation to your work and what has become most important to you at present?

KC: I don’t assess the work of other artists. Many younger producers ask me to critique their work or give feedback on their CD or a track online and I tell them I don’t do this. My opinion about another artist’s work means absolutely nothing.

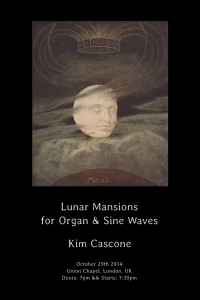

SR: Lunar Mansions is the first of your works I’ve encountered that combines an acoustic instrument with electronics. Could you talk about how this work came about, and how it fits into your current interests?

KC: A friend of mine recently became the music director for the Union Chapel in London which has a wonderful 19th century Henry Willis pipe organ. She asked me to write something for it so I decided to combine my work with interference tones and the organ. I knew the organ was tuned in equal temperament — which of course changed due to temperature and humidity — and being that I was very interested in just intonation my plan was to play sine waves tuned to just intervals that would interfere with or beat against the intervals played by the organ.

So for example, I’d have the organ play an octave and I introduced an interval that was a false unison. The organ pipes, in the front of the chapel, weren’t mic’d and I performed my sine waves through speakers situated in the rear so the entire chapel was activated by these interference tones or beats which can’t be fully experienced from the recording I sent you. The experience of this phenomenon in that setting was very meditative.

As an aside, the way people enter and behave in a church is very different compared to a regular performance space…there is a kind of quiet reverence that permeates the space and engages a different mode of reception in the percipient.

The idea for “Lunar Mansions” grew out of my piece “Dark Stations.” In that piece I arranged three speakers in a large equilateral triangle in which both the audience and a large subwoofer were placed inside. I noticed a curious effect when I played noise bands in the main three speakers and monaural beats in the subwoofer. The low frequencies in the subwoofer modulated the noise bands so the entire room seemed to pulsate. From what I’ve researched, this effect takes place in the basilar membrane and not in the actual acoustics of a space. I wanted to work with this phenomenon more and decided to see if I could incorporate it into my work with acoustic instruments.

The effect of acoustic interferences played in total darkness for a meditating audience is a powerful experience.

The inspiration for “Lunar Mansions” comes from the writings of Rudolf Steiner, La Monte Young’s “Dream House” as well as the visual art of James Turrell. This quote by filmmaker Gene Youngblood comes to mind: “the meta-designer creates context, not content” and has had an impact on my work for decades.

SR: Do you anticipate more works like this, or is it a sort of detour?

KC: Yes. I am currently arranging “Lunar Mansions” for different acoustic instruments for some performances coming up in the fall. I’m working on a version for three cellos which might be something I perform in Mexico City this year but haven’t gotten a green light for that yet.

I’m also performing versions of my “subflowers” CD which is coming out this fall on a small label in Berlin called Emitter Micro. I have two versions of “subflowers,” one for low-middle frequencies for regular speakers and the other for low frequencies which will be played in two subwoofers.

SR: What are your current projects–any concerts, writings, recordings, or other activities coming up?

KC: I’m writing an essay on spirituality in sound art, writing new versions of “Lunar Mansions” for various instrumentation and curating a film festival this spring in the Netherlands called “Drone Cinema Film Festival.” Despite the name the film festival is not a collection of aerial drone videos but a showcase of sound artists interpreting what a audio drone might look like on film. I am on tour in Europe this March where I’ll conduct a Subtle Listening workshop in Sweden and perform a version of “subflowers” at STEIM in Amsterdam.

SR: I think most, or at least a majority of the members of SEAMUS are attached to academic institutions and are often involved in teaching young musicians. I loved the quote from your infinitegrain interview: “I think all media arts and music schools should incorporate meditation into their curricula.” What other thoughts or advice would you have for music schools/teachers?

KC: There’s a funny story that a friend of mine who worked at Berklee College of Music told me a while ago. It seems the teaching staff at Berklee was very interested in inviting Ornette Coleman to the school to get his opinion on what they should be teaching young musicians. They flew him to Boston, put him up in a nice hotel, in short they rolled out the red carpet for him. There were PowerPoint presentations from teachers from various departments who got up and talked about their approaches to teaching music, they took him out for a fancy lunch and lavished him with praise and accolades.

At the end of all this fanfare they asked him what he thought they should be doing to better equip students for careers in music. He responded “Pray for me.” Nothing else, just those simple words — then he got up and left. They were less than amused and actually were quite angry after he left.

I’ll never forget this story as long as I live. The teachers were handed one of the most important lessons they will ever hear and they missed it entirely. The message was clear if you have ears to hear it. The teachers had completely forgotten about the spiritual, or intuitive, aspects of creativity and the need to nourish the artist in their materialist-oriented music curricula. The message is simple: art is not merely a mechanical or intellectual skill, it comes from the soul which needs to be nourished and they have forgotten this. We have all forgotten this. The fact they got angry about his response shows just how out of touch they are.

SR: Well, I wonder if you would think SEAMUS members are out of touch (or not?). A typical scenario that occurs at our yearly national conference, and in which probably many of our members are involved throughout the year, is where we create a “work” or “piece” that is meant to be experienced by an audience at a concert. Are we the enemy to your vision of what these types of communal gatherings could be? Is it a medium capable of greater transcendence, depending on the artist’s sensitivity and willingness to develop the “organs” you talk about? I’m not trying to be overly provocative here, but I’m interested in inviting our community (and myself) to examine what we do and how it could be different–your thoughts?

KC: I find it interesting that you chose the word “enemy” in your question since it implies a dichotomy. The dichotomy that exists for many is the spiritual/materialist one, which are really just polarities or modes of consciousness. In our society we privilege the materialist mode of consciousness over the spiritual/intuitive. And in the technological arts, such as electro-acoustic music, this is very obvious. Much of what is created in the technological or media arts foregrounds the materialistic aspect of the work. I see a need for a re-balancing our approach to creativity where the material is the carrier for the spiritual.

Kim has a new CD titled “subflowers – Φ” coming out this fall on Berlin-based label Emitter Micro. Check their website:http://emittermicro.com/ for more info this summer.

Suggested Reading List:

History of Consciousness – Gary Lachman

The Ever Present Origin – Jean Gebser

The Wholeness of Nature – Henri Bortoft

The Reenchantment of the World — Morris Berman

Saving the Appearances: a Study in Idolatry–Owen Barfield

Sound Between Matter and Spirit – Frits Julius

The Mysticism of Sound and Music – Hazrat Inayat Khan