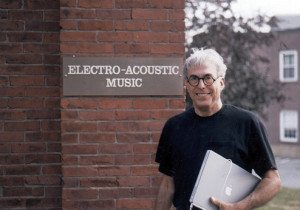

Friend and former student Paul J. Botelho conducted the following interview with electronic music pioneer, SEAMUS cofounder, and creative spirit Jon Appleton. Jon shares some frank and insightful thoughts on creativity, academia, and SEAMUS itself.

—Jon Appleton

PAUL J. BOTELHO: As a founder of SEAMUS, a pioneer and early proponent of the electro-acoustic idiom, and as someone who some have speculated as being the “inventor of music,” (laughs) where do you see the future of electro-acoustic music and music in general going?

JON APPLETON: Well it was only in Yekaterinburg, Russia that I was supposed to be the inventor of…I don’t think they called me the inventor of music, they called me the inventor of electronic music. They said that without me Michael Jackson would not exist—I was very flattered by that, and I didn’t deny it. But, where do I see electro-acoustic music going? Well, I still go back to what Steve Reich said many years ago, that electronic music will eventually merge with regular or whatever kinds of music. That’s true for most kinds of music that use technology, you see it especially in commercial music. I wish there was more acousmatic music. I find it difficult to listen to traditional musical instruments combined with an electro-acoustic track, e.g. the Davidovsky paradigm. He was a pioneer but so many of those pieces don’t work although I understand the reasons they seem so popular at SEAMUS. I really like the old European concept of electro-acoustic music, or, as they sometimes call it, sound art because it makes you think in new ways about sound materials. It takes me to a quite different sound universe.

PJB: Describe what you mean by the “old European electro-acoustic music.”

JA: I mean musique concrète or acousmatic sound art. Developing systems, developing new instruments, developing ways of organizing and creating sounds that are new and have not been tried before. They usually disappear as did the Synclavier – at least as a performance instrument. As Pierre Boulez said “the music world has a graveyard of musical instruments.” I think that’s true, but people have to keep trying. Sometimes they do it through software, sometimes through hardware. These days people are skilled at both. I just want to see people experiment with sound and not rely on fixtures such as the Davidovsky paradigm or even taking a musical instrument and processing key clicks or a bow on the back of the cello. Really, that’s so unrewarding and unimaginative. The exception is extended vocal techniques that can be found in cultures worldwide for centuries.

PJB: So, it’s not really that you’re describing any particular thing, but you feel as though there’s some kind of homogeneity in the approach to what is happening right now in terms of “serious electro-acoustic music?”

JA: Yeah, I do. I bet that everybody at a SEAMUS concert can’t stand most of the music. That’s how we feel about most music we hear. It’s only rarely that something catches our attention and that’s how it should be. But, I think there is a tendency for the SEAMUS judges to choose “safe pieces” and to program them because they happen to fit an existing paradigm. The conference organizers may happen to have a really talented violinist on their staff, so they promote pieces for violin and electronics. How about a really good piece for Hammond organ? Or, when you start to go through the categories of electro-acoustic music, how about guitar like Les Paul did? It seems to me that there are so many avenues of contemporary expression and older instruments, as well as the creation of new ones, that people fear trying. It’s not safe. I think composers in the academic world today are looking for safe and I don’t think that’s the way for the art to prosper.

PJB: Why do you think that everyone is attracted to safe? Does it have to do with academia?

JA: Yeah, I think that it does largely. It has to do with academia and it’s not just in electro-acoustic music. Take for example, the number of active opera houses in the world, or let’s say just in the United States. How many new composers are getting their operas produced? Yet, these are the very avenues that are pushed in academia because that is how their teachers were trained. These young composers instead of being adventurous, trying something new, going somewhere new, instead imitate what their teachers did. They have to write an opera. They have to write an orchestral sketch. What’s wrong with just making up a new instrument or playing a new instrument in some way and getting good at it? As a teacher, you help students get better at something they imagine instead of telling them “how it should be” or “how you learned it.” I never made my students do what I did. I noticed that some of them always liked to imitate what I did, particularly those programmatic pieces, but that doesn’t lead them anywhere because I do it better than they’ll ever do it.

PJB: (laughs)

JA: You know they’re just poor imitations, but someone that comes to me with something original that, perhaps I can’t understand, but I can tell that it is someone who is thinking about something original. For example doing a piece with a deck of cards or recording spiders in their web or just making up sounds that have never been heard before or that are rarely heard. I still really admire the principle of Cage’s Cartridge Music, to make music out of microscopic sounds that ordinarily we never heard before seems brilliant to me, a wonderful idea. Maybe it won’t work, but young people, young composers, need to be encouraged to try new things. That’s what they should be focusing on in school, not working to get a degree to take their teacher’s place in twenty years.

PJB: One thing though, and I think this leads back to the problem of academia, is that many music programs across the country require that you play traditional instruments. What about someone, as you stated earlier, who makes up a new instrument and learns it. That kind of person could not get a degree in music.

JA: That’s too bad. Your’re right, I agree, but on the other hand I don’t think there’s any reason to get a degree in music except if you really want to be a teacher. Not to be a teacher as a sinecure, someone supporting but without having a deep desire to help young composers discover their talent. If you want to be a teacher, then wonderful, go get a degree. I guess that you have to learn traditional musical skills, etc. But, if you just want to make music, then I don’t know that academic life…I think it squelches creativity as a rule.

PJB: Do you think that students need the traditional? Do they need that background?

JA: I think they only need the traditional if they’re going to write traditional music. I mean of course, you have to know how a cello works if you’re going to write for cello.

PJB: But in your vision you describe students that take on and create new instruments. What does an education look like for someone like that?

JA: Well I think that anyone who is a sensitive musician is already quite educated in her or his head. They know how to think about music. They don’t need to be able to know how to verbalize what they are doing, that’s a big mistake. All these courses and degrees that require people to write in the English language what it is that they are doing with their music. Why? Music is its own language and it works. It doesn’t need to be translated into English. I really believe that strongly. How boring to write a paper on Bartok’s fourth string quartet. Why not make that student sing the lines from the Bartok string quartet? Even if they don’t read music, they memorize those lines by hearing them and they can sing the first violin part. That seems a music education to me.

PJB: Is the label electro-acoustic still relevant?

JA: Yes, it’s relevant. It thrives in Europe, it thrives in China, at the Bejing Conservatory. I think that it is a valid concept, but I don’t think that many people in academia recognize it as a form because it’s so distant. Real electro-acoustic music is so distant from traditional music. Real electro-acoustic music explores new sounds. Popular music doesn’t explore new sounds.

PJB: Well, we’ve gotten, at least through the popular music sphere, to a point where almost all popular music, commercial music, is electro-acoustic in terms of its composition. So is the term relevant? No one says “I’m listening to popular artist X’s electro-acoustic music,” they say “I’m just listening to music.” Right?

JA: Yeah. We’re using this term popular music rather loosely. If you look on the fringes of popular music, like Brian Eno, then I think that Steve’s statement is correct. But…

PJB: What about your friend Miley?

JA: Well, we do have the same agent, but we don’t talk to each other (any more) because she really hates my music.

PJB & JA (laugh)

PJB: OK, let’s shift gears. As someone who has been active in the electro-acoustic field for many years, a founder of SEAMUS, and as someone who has attended many SEAMUS conferences, what does SEAMUS get right and what does it get wrong?

JA: It allows mostly young composers to meet other young composers. I think that that’s a very valuable, that’s really the most valuable part of it: probably more important than the concerts or the occasional paper sessions.

What does it get wrong? Well, there’s never been an attempt by the organization to reach out to others that aren’t academics. It was founded on the principle that it was going to be inclusive of people who just made electronic music, whether they made it at home or whether they had academic positions. I know that people with academic positions often have the funds to travel to the meeting, but I just think that the organization should broaden the base for it to meet its potential.

PJB: So how do you do that?

JA: Well that takes one-on-one contact. Everybody knows someone in her or his community that makes some kind of electro-acoustic music. I meet people even here on the island of Kauai who say “oh, I make electronic music.” OK, fine, let’s hear it. Mostly it’s new age, but sometimes it’s drum machines, but sometimes it’s not. Those people wouldn’t feel comfortable in an organization like SEAMUS because they’re not traditionally musically educated and they lack the vocabulary to discuss their work. Yet, they have musical ideas that could very well be exchanged. I feel that it takes individual members to go out and try to convince someone to try it out.

PJB: All right, I have one more question for you. Recently you’ve been composing many purely acoustic works including your Scarlatti and Couperin Doubles and your soon to be released CD – Jon Meets Yoshiko. Maybe tell us a little bit about where you’re going now as a composer and what we should be anticipating as an audience.

JA: (laughs) Well, OK, so this may be a little too long of an answer. I was trained rather poorly in music, it was my own fault, but in any case when I started writing so-called “serious music” in graduate school in Oregon and Columbia University the serial technique was considered the future. The pieces I wrote that way, well, they’re OK, but I don’t like them and I hated writing them. That didn’t seem to me to express my musical soul. Then I stumbled upon electro-acoustic music, you know I worked in the Columbia-Princeton studio and worked with Ussachevsky who didn’t teach much but was very encouraging. That’s what teachers need to be: encouraging. I later found out that he wondered why I was such a conservative composer.

PJB & JA (laugh)

JA: But, in any case, I found a niche, whatever it was. It was programmatic electro-acoustic music, it told kind of a little story. I used voices, found sounds, electronic sounds and mixed it all together. I don’t think that many people that I know were doing that at that time, at least from the music that I heard and I heard quite a bit. So, that’s what I did and I loved doing it. I did it for many years. Then gradually, starting about twenty years ago, I found that I was repeating myself, and not only repeating myself, but the pieces just weren’t as good. I think that the last really good piece I did like that was Sheremetyevo Airport Rock. You know I think that young people sometimes have a spark of originality and I had it at that point and I did something unusual. That doesn’t always follow. It doesn’t always sustain, originality doesn’t always sustain in a composer. By chance, I was teaching at the Theremin Center in Moscow and I met some wonderful instrumentalists who said “why don’t you write for us?” So, I didn’t want to write twelve-tone music, serial music, for them and I didn’t want write minimal music because I don’t do that. I just wrote the kind of music I’ve loved all my life with my own little twist in it. It wasn’t hugely original at all. But it was solid and that was good. So that’s what I’ve been doing ever since. The latest CD that’s coming out this December is four different piano pieces over the last four years that are played by a wonderful Japanese pianist, Yoshiko Kline. I like this music. I might get tired of it, but it’s not why I do it. I do it just for the pleasure of writing it. And, of course, I love to hear it performed, but once it’s performed I usually forget about it. I’m more interested in “what am I going to do next.” So, right at this moment I’m writing a piece for children’s choir. Not for professional children’s choir, but an amateur children’s choir with piano. That gives me a lot of pleasure. I’ve done a lot for children’s choirs in the past and it’s something I think I’m reasonably good at so I’ll do that. I think that what we should value in people is the continued creative urge. I think there’s nothing as sad as people who have given up composing. Why did they give up composing? Because they did not get the approbation that they wanted? They couldn’t earn any money from it? OK, but, I think that if you are a genuinely creative person, as a musician, you will find a way to express yourself. In any case, you won’t be happy unless you are doing it.