By Lou Bunk —

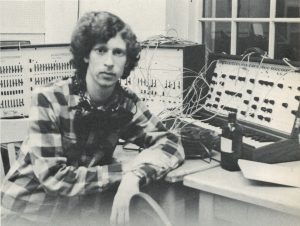

Eric Chasalow is a composer known for creating a vivid kind of “super-musique concrète ” that combines traditional instruments with manipulated pre-recorded sounds from any source imaginable. He teaches at Brandeis University, where he directs BEAMS, the Brandeis Electro-Acoustic Music Studio.

This past February, Eric and I met in his office at Brandeis and sat down for a good long conversation. While I came with some prepared questions, we freely drifted among many topics: the community of the Columbia-Princeton studios, what a sound carries with it, capturing the energy of Jazz solos, audience, Sound Art, conceptual art, aging, and what has stayed the same in Electronic Music while technology has changed. Below are some excerpts. Returning to Brandeis to spend some time with Eric was such a treat, and quite meaningful for me, as he was my dissertation advisor and a mentor in electronic music.

* 1 *

You wrote that “studios are like communities” in a description of your oral history project: “The Video Archive of the Electro-acoustic Music”. Could you describe the community of the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center while you were there? Who were your colleagues and mentors and how did being a part of this community impact you as a composer and musician?

It’s a big question… and I have to give just a little background. I discovered electronic music in high school. There just happened to be a copy of “Silver Apples of the Moon” in the band room, and I thought “this looks cool, what is this?” And at the same time, this local music store lent me an Arp Odyssey, which is like a MiniMoog. They just said, “Here, try and play with this.” They were looking for publicity because I had won an award for Jazz guitar.

Anyway, fast-forward a little bit, I got to college, and I started studying composition with Elliott Schwartz at Bowdoin. I was a student at Bates and he had a studio over there with an Arp 2600. My junior year, I spent at New England Conservatory and worked with Bob Ceeley on an ElectroComp synthesizer. I made some tape pieces, and I thought this is a big part of where I want to go. I didn’t know how it was all going to get reconciled with the other music I was interested in, which was still Jazz… or with what I was interested in doing with instruments, although pretty early on I heard Davidovsky’s Synchronisms No. 1, and I was interested in that.

Track 1: Eric talks about studying at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center in the late 1970’s, and getting to know the people and the equipment.

Working there took a certain kind of concentration and dedication. We knew it could be a little bit easier because things were moving towards computers, and we were working in the analog studio… You got the sense that the people around you are all in the trenches together. And so that engendered a very strong sense of community. Plus I was a newbie at that point, and everyone’s trying to help. The community at that time was large and included Pril Smiley, Alice Shields, advanced student/teachers Arthur Krieger and Maurice Wright, engineers Peter Mauzy and Virgil deCarvalho, and lots of students passing through.

Milton [Babbitt] would show up to work on something, not very often at that point because the RCA wasn’t working. I would play things for him, and he was very generous with me. I was incredibly sheepish about what I was doing. I had classes with Mario where I played things, and Vladimir would ask me what I was doing. He really cared about that, thinking of himself as one of the inventors of this, but he was also a very curious person—earlier he was constantly jetting around the world to find out what Stockhausen and Berio were up to. If there was one thing these people had in common, and I mean Mario and Vladimir especially, Milton in a different way, and Bülent Arel, who had been the very first studio assistant, is that they were crafts people. Many of them would make furniture or do woodworking projects. And so splicing tape with your hands, it was this kind of manual skill, very much about inventing things, putting it together.

* 2 *

Do you think anything is lost from learning in such a physical way, using actual objects to make these sounds, and then all that going into the computer? Do you think anything is lost in the translation, or lost in the art that is being created?

It’s different models… you know, there is lots of software that emulates those physical objects. You see the knobs, you move them around. So in that sense, I think it circled back. There is so much interest now in analog synthesizers, all these companies building them often better than they were built originally. I think a lot of people felt when we moved from that tactile environment to software-based models that something was lost. And I am not so big on nostalgia, although I do believe in certain traditions, certain ways of working. So if I really answer your question literally, “Is something lost?” The answer is yes.

What is it, do you think? What is lost?

Well it isn’t as if what we have now is terrible. There is the immediacy of working with a machine, and with the models and software now, we have that. People would argue that analog synthesizers and analog devices have a different sound. Buchla, Moog, Serge, ElectroComp, Oberheim, Sequential, Roland, all of those have a different way of working, different models, and each of them is a different instrument, different sound.

Do you think what is lost is the way you interact with those instruments, the performance aspect?

Do you think what is lost is the way you interact with those instruments, the performance aspect?

I agree with you… yes, that is what is lost. The physicality and muscle memory. The way we physically interact with instruments is really important. I didn’t used to think about that a great deal. I think I’m not alone. People from my generation and before who were working in those studios, we were looking at that equipment as a way of making sound. We were so focused on the sounds. And a lot of us were pretty quick, as the technology changed, to replace it with something newer… moving into MIDI instruments. And then gradually a lot of us realized, oh, they’re different instruments they have different capabilities, different ways of working. You shouldn’t just be discarding one and going on to the next. But it’s not like a violin where you have 300 years of tradition or more.

I am not saying anything earth shattering here that even between Moog and Buchla… you know, Don Buchla very deliberately was thinking about building a machine that was not keyboard-based. He cared about that a great deal, as did the people around him, Mort, Pauline and Ramon, who were at San Francisco, and they were thinking very differently.I mean this goes to the whole question of community too, because of having gotten to know a lot of these people over the years… you know these people were my heroes, Lou. I hadn’t met them, I read about them in books and I heard their music. And the exciting thing was getting to meet them, many of them, and then have some sort of relationship where you explore things together.

Track 2: Eric tells a story about working as an audio engineer on a performance of Morton Subotnick’s “Ghost Pieces”

* 3 *

Are there certain tools that have stayed with you over the years, even as the technology has changed?

The basic ways of thinking about sound absolutely did not change. When you start working in the studio, especially in an environment where you have to make everything, whether it is literally by hand or with software, where you don’t have a lot of presets and you can’t turn things on and let them go, you have to think it through. The advantage is you learn a lot about the microstructure of sound, and it focuses your ear on tiny nuances.

So very early on, I started thinking about how you make a phrase in terms of envelopes. This was a revelation. This was a big thing working with Davidovsky and he talked about it some. He didn’t make a huge point out of it, but his music did. Different envelope types, different kinds of attacks, sustains, and decays, and incrementing those things in different ways is so powerful. I am always trying to do that with whatever instrument. It adds another layer to the counterpoint of a phrase. That’s something I absolutely hold on to.

For you, what else has stayed the same? In your more recent pieces, have you used similar tools or concepts that you would have used in your earlier pieces? Or maybe not?

I’ll tell you Lou, one of the things I am doing these days, that I never would’ve done years ago, is applying mechanical processes to material. Very rarely in the past would I take a phrase and do a literal time augmentation. Or a literal inversion or retrograde. I did that stuff to see what it would do, what it would create that I could use. But I’m doing it with much bigger chunks of stuff now, because we have the tools to do it without thinking too hard. But ultimately it doesn’t matter whether your processes are random or mechanical, what matters is what you discover and choose to put into a piece.

Track 3: Eric talks about Elliott Carter and musical layers moving at different rates. As he puts it; “an illusion of things coexisting that can’t possibly coexist.”

* 4 *

In an ASCAP Audio Portrait, you say that Jazz “was the first art music that really excited me” and in many of your pieces what you are “going for” is “a kind of energy that you get from great Jazz improvisers.” Can you talk a bit more about how Jazz has influenced your electro-acoustic music, perhaps from its forms and motifs, or other musical elements?

Well, I have these elements that are like Bebop riffs, or Post-bop riffs, or sort of a tonal bop, that kind of energy, with streams of 16th notes in a lot of my instrumental music, and in various places in the electro-acoustic pieces too. One of the things I struggled with was having the technique to play saxophone—guitar at a certain point—really fast and in an intelligent way. It is not an accident I was listening to Bird and Coltrane and then going into the city to hear Sonny Rollins multiple times. You know, the giants. I just found it tremendously exciting. One of the things you do, especially when you are younger and hear something that is tremendously exciting—you want to imitate it.

Track 4: Eric talks about trying to play Jazz but realizing “I never had that kind of technique. I loved the music, and I tried and I tried. But if I slowed things down, I could write out ideas that I could then give to other people to play really fast… and the thing you can’t do, is what you want the most because you can’t do it.”

That pushed me to try and do what I couldn’t do as a player, in like every piece I wrote. I entered this whole other world, this subculture of contemporary music which is not the subculture of Jazz, but where there are plenty of people who had experience with Jazz, and certainly a lot of people loved it.

So sometimes we talked about reconciling these two traditions, because we were very aware of them being different. Russ Pinkston, who was a classmate of mine, always talked about ways of dealing with tonality in his music. He was a really accomplished rock musician, in a band, with an album. He cared about that part of his life. And I cared about the other stuff I did too and thought, “How do I use this stuff I love? Maybe I can’t improvise tonal Jazz very well, but I know that music, and I care about it, and I can use it. Where does that sit in a world with this other music that I have learned about? Davidovsky, Carter, Martino…”

Outside of the surface energy you are talking about, is there something in the more extended forms of Jazz that you use in your own music?

I guess it’s a good question Lou. I don’t think so. You know, I am thinking of dramatic forms that come more from classical music. In the Jazz tradition, the various traditions, you have chord changes, and then a lot of the invention has to do with how you play with other people. How you feel it, how you feel time. But certainly when you are improvising over those changes, you don’t worry… I mean that kind of repetition, where you cycle through the changes again and again is built into that music, and no one thinks twice. Whereas when I was growing up, repetition in my sub-subculture, as opposed to downtown… people really avoided repetition. Or you thought about it very carefully, about how you used it. So no, I don’t think about that [extended forms]. I think about the materials themselves, not just the surface energy, but the kinds of motives and themes that I write absolutely are related to improvising on Jazz instruments.

Track 5: Eric talks about “quotation,” “re-contextualization,” and “getting somewhere else” in his piece ‘ Scuse me for electric guitar and tape.

Were you trying to capture the improvisatory nature of Jazz, and write it down?

I did think about it, but you know, that spontaneity is important when you are in a room with great improvisers, and they’ve got their vocabulary. It is not that they take it from nowhere, we know better than that, right? But they are able to put it together on the spot in a way where surprising things happen, and as a listener you go on that journey, and it’s like… oh my God.

Track 6: Eric talks about meeting Branford Marsalis and asking him about a concert he played with Sonny Rollins.

But beyond those few times [hearing Jazz played live] which are really memorable, most of my experience was digging through the classic recordings of Jazz. So I got to know Giant Steps and everything from Bird, Dizzy, Miles, Stan Getz, Chet Baker… I spent so much time listening, and that stuff gets in you, and you can go back to it, and hear it again. So when I put on Giant Steps, because it is iconic, it is something like a Beethoven symphony, you come back to it again and again. We have in the library, transcriptions of a lot of the solos Coltrane recorded. There are multiple takes. I have played through them, and I’ve looked at them, and they are all amazing in their own way. But the one that is on the record, which is in my head, I still find it extraordinary.

I never really thought about it until you asked me this question, but essentially what I’m doing is to capture recording, and trying to write something that is like a Jazz solo, that sense of structure—that it really takes you somewhere. And the best ones, they might have some formula, but there isn’t much, and there is nothing wasted, and it gets you there eventually. If it repeats, the repetition just reminds you where you have been and eventually it really builds to something extraordinary. And so you get that live, but I still get it in the recordings of those solos. I never thought about it consciously the way I am talking about it now, but it is sort of like recording a solo when we compose. I can slow it down, and make it work, because I can’t do it in real time. [laugh] I mean I can do it a little bit in real time. Maybe I can do it more now.

* 5 *

In a recent article you wrote for New Music Box titled “Electroacoustic Music is Not About Sound” you wrote: “My most naïve idea may be that anyone is willing to concentrate and truly listen through a piece of music at all. If we cannot make this assumption however, we lose musical experience, so to abandon this hope is to abandon music.”

Can you talk more about that idea, and if you are writing music for an ideal listener?

Yeah I can, only at the risk of quoting Uncle Milton again. These things come out of my head all the time; “I can only write what I want to hear.” So I don’t think about some external audience. And when I teach composition it is always a struggle with young composers who talk about audience, which doesn’t mean I think you ignore your audience. I am trying to capture ideas—and to follow musical ideas you have to concentrate hard over a period of time. You have to go on that journey. It is a narrative form.

In order to achieve any of that you start from the assumption, when you have a piece performed, that anyone who is listening is really listening. And I guess I am sort of bemoaning the fact that it is a learned skill. And I don’t think it is overstating things to say that most people don’t grow up learning it. To some degree that has always been true. And I am like everyone else. If I am in a concert hall, I have to put myself in a state of mind to be with a piece. And I don’t always do it, but I can think of times where a performance was so extraordinary that it demanded I do it.

We live in a world where everything is experienced in five second clips, and maybe we need to respond to that in some way as artists. This is what is so valuable about concert halls, and live music experiences—where you make a space for a piece to exist, but people have to learn how to have that experience.

Do you learn by doing it?

Yes. I think with some guidance. You learn by doing it, and being rewarded. And it is rare that we feel real gratification for doing it. It can be work too. Which I don’t think is ideal by the way. What we all long for is that experience where you get with the piece of art and you fall into it. Right? You lose yourself in it, and it shows you something about the world. And that takes a certain kind of concentration and letting something unfold over time.

There is a risk as well?

For the listener.

Because it may turn out to be something you may not like?

Yeah…how many times have we been in a concert, and we get up at the end and say “well there is an hour of my life I will never get back?”

* 6 *

In our pre-interview, you talked about Musique Concrète and how you are interested in “what a recorded sound carries with it.” Can you talk about this a bit, perhaps squaring this idea (or not?) with the main topic of that previous article (Electroacoustic Music is Not about Sound).

Yeah, those things seem to be in opposition to one another, don’t they? I remember our friend Hillary Zipper when she was studying here, and she would bring me music on her violin. She was just scraping a bow as slowly as possible for a long period of time. And she just really, really loved the experience of that sound. And that is legitimate—but for me it is not enough. And I used to argue with Hillary, and I have argued with other people about this. I argue less now about that. Cage always said we don’t have to do anything, the world is full of beauty. I am paraphrasing. There is sound all around us and we need to be awake to it. This is the Buddhist approach to the world, to be awake to the world, which is an idea that I really value. I do think we need to be awake to our surroundings, and aware, and to not be filtering out all the time, narrowing down.

I guess what I’m saying Lou is I am not interested in that as a thing unto itself. Although, the older I get, the more I am willing to sit and just listen to a sound and find beauty in that. But as a composer, what is valuable to me, especially if I am trying to do a fixed media piece, is that connection we make to sounds that we recognize. So I am less interested in abstracting so totally that the source no longer matters. It is a little bit like figures in painting, right? When you see an outline of something and your brain can make those connections to something in your own memory, your own experience… that’s powerful. So if we hear an electro-acoustic piece and there is something in it that sounds like someone humming, but maybe it isn’t? You can lean one way and it is abstracted, and leaning the other way it comes into focus, and you recognize what the sound is. And these associations we the listener make with what we are hearing… it is a valuable aspect of doing things in electroacoustic music.

It is one of the reasons that those tape and instrument pieces started happening early on, because the live instrument is something we can connect to. We have a history with it. Solo violin carries the weight of all solo violin music ever written, or piano music, or string quartet. It is there as a point of departure. When you get to fixed media pieces, the sound source has the weight of every association we can make with it, whether it is a train—which is somewhat ironic because Schaeffer talked about not wanting you to hear what that source was, but rather the quality of the sound. But the fact is, the source itself is very powerful because of what it invokes and evokes in memory.

But that is just a point of departure for me. The sound quality itself, for me as a composer, it is not enough. I then have to work very hard with everything else at my disposal to create layers of meaning in a piece.

What carries it then? If it is not the sound itself that’s carrying the piece forward, giving it shape, is it the combination of harmony, melody, rhythm, form, and then sound is fit in, or is sound somehow part of the structure?

Yeah, ultimately it is sound, but when we talk about sound here, we’re talking about sound quality. Is it the sound of a string being plucked, or a can being kicked down the street? What I was reacting to in that article is that I have heard too many cases where composers get seduced by the quality of the sound. It seems to me they have given up on aspects of rhythm, or pitch. And by pitch we could mean how you manipulate the spectrum, it could mean all kinds of things, right? —the particular tuning of that sound. Whereas if you pay attention to every aspect of that sound, you could create very powerful music.

I am just saying, listen to what is happening with all the elements. Go beyond yourself as a composer. Work very hard. I know there are some people who read that article and thought I was being incredibly naïve, but what I am trying to do is to separate out [musical] elements that are hard to separate. I heard an awful lot of talk about how we have new tools, and so we convey meaning in a different way. We need to prioritize timbre, so we need to simplify pitch. Well that isn’t necessarily true.

* 7 *

You also talked about how timbre can heighten what you do with pitch and harmony in reference to the slow movement of your piece Are You Radioactive, Pal?. Can you talk about how this relationship between pitch and timbre plays out in this movement?

You also talked about how timbre can heighten what you do with pitch and harmony in reference to the slow movement of your piece Are You Radioactive, Pal?. Can you talk about how this relationship between pitch and timbre plays out in this movement?

It is so hard… we artificially separate pitch and timbres as if they are separable. They are not. They’re both conveying an idea. You quoted me saying sound can’t carry an idea. I meant by itself. Sound is a complex construct. It is helpful to separate out those elements, to concentrate on how they are working in a piece. So in that piece, and this is true in any piece, what I am saying is back to this idea of counterpoint of different elements. I will write a line for an instrument thinking about pitch and rhythm sort of simultaneously. And very often I will be thinking about the timbre at the same time.

Track 7: Eric describes his editing and composing process; “when you make an electro-acoustic piece, you are doing a realization of a performance, and you have got to put in there the energy and the physicality.”

Do synthesized sounds, like the ones in this piece, carry something with them as well? How you described a train sound carries a train, do synthesized sounds carry something in a similar way? Perhaps to the instrument that created them or…

Potentially yes. What is interesting is that we worked so hard in the early studio to make things sound sensitive and instrumental in quality. We wanted it to have these nuances. But we never thought that synthesized sounds would then carry… would be in people’s memories. My son, he writes EDM tracks and there are these pad sounds, and other kinds of synthetic sounds that we tried to avoid, we thought they were cheesy, we wanted to get rid of them. And it is just part of their vocabulary. Like a violin sound is part of our vocabulary, those sounds are part of our vocabulary now too. Once it is there in the culture, in the sphere, people hear it—it becomes a part of the way we communicate.

Our memory of sound… that is what I am talking about by putting something into a piece that carries something with it. My older pieces for instrument and tape, when they are played now, people hear them and say, “Oh, I love those cool retro sounds.” Or, “I hate that, why do you keep using those old sounds?” I mean, I get that too.

When you were working with the sounds of this more recent piece, were you thinking about that history of those sounds?

You mean the saxophone piece?

Yes, Are You Radioactive, Pal?

No, no, it is just sort of my repertoire. I am trying to move from what I know to something else and tweak them. I don’t feel as if I am honoring some aspect of the history of electronic sound by making that piece sound that way. I don’t want them [the sounds] to stand out. The focus there is on the saxophone, and on the way those sounds blend with, or are distinct from the live instrument.

Particularly in the second movement, the instrument and the electronics overlap quite a bit, and not seeing it played live, there can be an illusion, where you get tricked into not knowing where the sound is coming from.

Well that is the tradition that I really wanted to operate in, and when I make those pieces I still do. That was the cool thing about a couple of moments in the flute synchronism where a sine tone seems to come out of the flute. Or the beginning of Synchronisms No. 6 is the famous moment where the piano makes a crescendo. If you are thinking about that all the time, oh… how can I do that differently? —you invent a lot of different ways of doing things like that.

For you, what’s valuable in that particular technique? Or what is interesting to you about that way of writing?

What is valuable to me is in a live concert situation, seeing the traditional instrument and hearing it change in a way that is surprising. And then after a little while… you know, we have enough of those pieces now that it is not totally surprising, but to have something that can be so locked in, that it sounds like you are manipulating the sound of the instrument with live electronics. And yet, the live electronic pieces usually don’t have the same kind of tension that you get with tape and instrument pieces.

The dialogue, you mean by tension?

I don’t even think of it as a dialogue. The live player has got to be right there to synchronize if you don’t have a click track, and I hate click tracks. But I haven’t made one of these pieces in a few years now. I got a little burned out on them. So I put out a book that has all of that [Eric Chasalow: Works for Instrument and Tape (1979-2013)] and said “OK I am closing a chapter, and maybe I’ll do another one. But not now.”

* 8 *

Where have your interests gone recently?

Where have your interests gone recently?

I love setting text and working with the voice. That latest piece Elegy & Observation is found poetry from all different sources. Doing things that have other dramatic elements in them interest me. I am finally at a point where I feel like I could do a Sound Art installation, which gets away from the narrative. I haven’t done that, and would like to tackle that set of problems.

What is drawing you to Sound Art?

I get bored with myself. I think the whole other venue draws me to it. I think people in the visual arts world are much more open to different possibilities. And there is another aspect, and I admit it is ego, but I hear a lot of so-called Sound Art, and I don’t find it very interesting. I am sure the artist had an idea, and loved doing it, or worked hard to do it, but it doesn’t get anywhere that I find revelatory. It doesn’t make you hear differently. And I want to try to do that. And maybe I will fail. Certainly I will fail some.

Are you imagining something that would be an installation in a gallery?

Yeah, installation art. Also I am really interested in collaboration, and collaboration is really hard. I have done some of it. So I can imagine doing an installation where I am doing sound and working with a visual artist or sculptor. Yeah absolutely.

And I think it is absolutely legitimate. Sound Art artists self-identify and usually come from the visual arts. Although I think that is breaking down more now. Why shouldn’t we—having all this experience and training and acute hearing, and having worked at this our whole lives—be doing that?

Are you attracted to the idea of working with a concept?

I am less against working with concepts than I was.… I am not anti-anything anymore, to a degree.

You used to be? [laughing]

Look, most of the time things are not transformative experiences. It is hard to get there. And maybe a piece that I don’t find transformative, someone else does. That is perfectly legitimate.

With the chorus and tape piece [Elegy and Observation], I really wanted to have a very poignant text that addressed climate change. When you have a text, you can do things thematically. I have nothing against generating concepts. The idea of conceptual art however, most of the time, once you know what the concept is, you can throw the piece away. That I have a problem with.

Although I have started to find great beauty in simplicity. Maybe this is part of aging. The idea that you can have a single stroke of calligraphy and it can be very beautiful. It has a certain kind of energy, and that is very hard to capture. And you try to do it again, and again in order to get there. And when I was younger, I appreciated that less. I intellectually understood it, but I found it hard to get there. I understand it a bit more deep down now, sort of in my soul, the beauty of simplicity.

Track 8: Eric talks about “Body Tracks” by conceptual artist Ana Mendiato, where she uses her blood to make body prints on paper.

I was looking at this work. I’ve seen those pieces on paper in the Rose collection as long as I have been at Brandeis, which is almost 30 years now. And I sort of thought, oh what an interesting idea, and then I would walk away, and not really look at it. And now I find myself standing in front of it… in a way, it is like the sound carries… getting back to the idea of a sound carrying an idea all by itself. Right? Just being with this one thing that’s beautiful, intractable, and indivisible in a certain way. It has its own nuances, and that has got to be enough if you are willing to stay and witness it, and absorb it, and process what it is you are looking at. Can it speak?

It has come to a point for me now, where with those pieces, I can do that. And I can do it a little bit more with sounds too. But I am not creating things that I would call a piece that consists of that kind of work, not yet anyway.

You have to get a little older?

Yeah, I’ve got to get a little older. I am hoping to get a little older.

* * *

Lou Bunk is a composer and improviser living in Somerville MA. He directs the concert series Opensound, co-directs the ensemble Collide-O-Scope Music, and is Associate Professor of Music at Franklin Pierce University.