— By Elizabeth Hinkle-Turner —

I have known Carla Scaletti virtually all of my compositional life starting with her appearing “in the distance” as a quietly awe-inspiring presence (so many people spoke so reverently of her creative intellect and thoughtfulness) in the Computer Music Project of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 1986. I was privileged to work with some of the early incarnations of her Kyma System at a Sound Computation Workshop with the CERL Sound Group towards the end of my studies at UIUC in 1991. A year later I recall sitting next to her at a SEAMUS banquet trying very hard not to let on to everyone how miserable I was after my first chemo treatment, and listening to her discussions with others at the table helped to focus me. There have been many subsequent conferences and workshops and interactions in between. Finally, in 2011 I was asked to write a chapter about her for an upcoming text (Laurel Parsons and Brenda Ravenscroft, eds. Analytical Essays on Music by Women Composers, Volume 4, Oxford University Press, forthcoming), a project which has just been completed by the editors and authors.

Though I have joked with Carla that sometimes I feel as if I am the “Robert Craft” to her “Igor Stravinsky,” she has been unfailingly polite and generous with her time, her thoughts and her resources. I have found this to be a universal about Scaletti: when asking other composers and colleagues about working with her, the Kyma System, and her company, Symbolic Sound (kyma.symbolicsound.com), they speak of this generous responsiveness, avid curiosity, and genuine desire to collaborate in every way. In this interview (an emailed dialogue with the composer and inventor), I enjoyed asking her about things we had never previously discussed and only just generally touched upon in earlier conversations that directly relate to her recent 2017 SEAMUS Award acceptance speech. Let’s continue the discussion!

(Hinkle-Turner’s questions are in bold print, with Scaletti’s answers following in regular print.)

Carla Scaletti 2017 SEAMUS Award acceptance speech

Carla Scaletti performing SlipStick at SEAMUS2017. Photo by Scott L. Miller, SEAMUS President & organizer of the 2017 conference at St Cloud State University

On your personal homepage (carlascaletti.com) you begin with a Mu-Psi manifesto. You write that it is “sound art that seeks to transcend the personal and to express universal concepts, patterns, and processes” and continue with an explanation of how it is analogous to science fiction. For as long as I have been familiar with your composition catalog, your starting point of “a Mu-Psi sound work begins with a hypothesis, a ‘what if’ premise” that then explores the ramifications of the premise has been a primary creative interest. Am I correct in that assumption? Can you provide us with a narrative of how this started and emerged as a primary creative interest?

I think that concept had always been there, but I hadn’t noticed it until you asked me a question about it for your first book; you asked me if there was anything that characterized or unified all of my work, and that’s when I noticed that there had always been a thread of science and mathematics throughout the work I had done up to that point. I was pretty excited to discover that there was a unifying theme because it made it clearer where I’d been and gave me a guide of where I wanted to go next, so thank you for asking that question!

Where did it come from? My father was a scientist, we were very close, and I grew up thinking that I would be a scientist too. It was only at the last moment when I had to choose a major that I chose music composition, instead of a scientific area.

To this day, I’m often able to access that elusive sense of transcendence we’re all seeking by reading articles in Science magazine. I think there is something about science and the arts and education that let you become part of a project much larger than any one individual could finish in one human lifetime. I remember being amazed to find out that it took several generations of architects and builders to complete some of the cathedrals in Europe. In a way, we too are contributing to more abstract edifices of knowledge by contributing to the arts and to scientific research. And in education, you can trace the lineages of your own students and their students and reflect back to your own teachers and their teachers and feel connected to a long tradition that stretches backward and forward in time.

For me, the ultimate goal for making music is to be able to give people a sense of transcendence, even if just for a moment or two. That’s what I’m always trying for anyway.

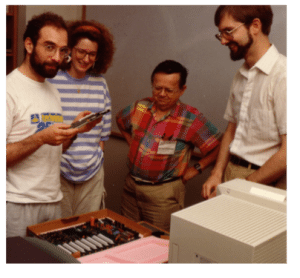

Kurt Hebel at the 1991 CERL Sound Group Sound Computation Workshop explaining the scalable architecture of the Capybara. Left-right: Roberto D’Autilia, Elizabeth Hinkle-Turner, Dick Robinson, Kurt J. Hebel

Listening back, listening forward [resources about ICMC 2015 Keynote address]

At ICMC 2015 you gave a keynote address “Looking Back, Looking Forward” providing an overview of a shared history in creative computer-based exploration and then moved to a more specific discussion of the early days of your work which lead to the Kyma system and the formation of your company. What are a few of the major pivotal events, people and/or experiences that were essential to the emergence of Symbolic Sound?

In retrospect, everything that happened prior to that was leading up to the emergence of Symbolic Sound.

My parents were very entrepreneurial educators; they loved starting new programs, even when it meant taking a less traditional career path. My father left a tenure-track position at the University of Minnesota to help start a new medical school, initially housed in a re-purposed 7-up bottling plant at the University of New Mexico. My mother started several alternative schools within the Albuquerque public school system, to educate the “misfits” who were on their way to dropping out or being expelled, and she started the first computer literacy classes at her high school even before she knew how to use a computer herself (I remember the two of us learning LOGO programming together during one vacation). So they were constantly experimenting with new formats and derived energy from the excitement of building new programs.

The CERL Sound Group also had a very “high tech-startup” atmosphere. It was up on the top floor of the Computer Based Education Research Laboratory, accessible only by metal fire escape stairs so “adults” rarely went up there. Lippold Haken and Kurt Hebel were unusually independent, self-motivated, and creative for undergraduate engineering students; they loved the work so were there late every night and on the weekends. Don Bitzer, the founder of CERL, brought a lot of money into the university through his patents, and he supported the music lab in part because the Sound Group could always provide some entertaining demos for what he called the “dog and pony” show he would present to grants agencies and investors. In between those rare dog and pony shows, we were left alone and unsupervised for long stretches and had a budget for buying parts and designing/building PC boards. It was an amazing opportunity! But it’s not every undergraduate who would know what to do with that opportunity. Kurt and Lippold were pretty amazing individuals. Even as teenagers, they already had their own ideas, the motivation to apply what they were learning from their classes, and the ability to teach themselves whatever they weren’t learning in school. For me, discovering the CERL Sound Group meant I’d finally found some people I could discuss Computer Music Journal articles with! It was so inspiring to be in that atmosphere, learning things, making things, and actually seeing them being used by people, that, even though I had finished my doctorate and was already teaching in the School of Music (I was covering John Melby’s course the year he had a Guggenheim grant), when Lippold offered me a research assistantship at CERL, I didn’t hesitate. I turned down an offer from the School of Music to teach music theory courses the next year as a visiting assistant professor and became a student again (this time pursuing a masters of computer science).

Working at the CERL Sound Group was actually good practice for starting our own company. At CERL, we had to design, plan, program, order parts, call suppliers; we even had “customers” we had to support (the students and faculty who worked in the open studio up on the fourth floor). So in a lot of ways, we already knew how to run a company even before we started Symbolic Sound.

But as is often the case in life, taking a risk requires a little push. We would have been happy to continue pursuing our research at CERL; I had started applying for grants when Bitzer’s patents began to expire. But like many successful people, Don Bitzer also inspired his share of envy (he often made a point of how independent he was, since he had large grants from industry partners and NSF, and his patents) and when his money started to dry up, there were others at the university who were eager to push him out. He ended up with an endowed chair at North Carolina, but everyone else at the lab was given a year to find another job. Kurt and I had already talked about starting our own company. But losing your job is a good motivator! The non-academic employees got unemployment benefits but part time academic employees (I was a quarter-time research assistant at the time) were not eligible. Lippold felt bad about that so he told me unofficially that there was no reason for me to show up at the lab anymore and that I should go home and work on Symbolic Sound full time. So thanks to Lippold, I had a subsidized year where I could work full time in my new office (which was the second bedroom in our fourth floor student apartment). The UPS and FedEx employees got a kick out of delivering parts to a student apartment and taking away large boxes containing Capybaras destined for addresses all over the world. Last year, we got a delivery at our current offices by one of those guys who recognized me and had a big smile on his face, “I remember you guys! You used to be in that little apartment!”

I never expected to start a company; I thought everything in my life was leading up to becoming a music professor. But in retrospect, it is easy to see the events and experiences that led into Symbolic Sound as a nearly inevitable consequence of my early influences and my collaboration with Kurt Hebel. For me, the work has always been the essential thing. And we’ve been able to pursue our research, to continue learning, to make music, and to teach others through Symbolic Sound. That’s everything that I had wanted to do at the university, and I’ve been lucky to be able to do it as an independent artist/developer.

I guess the reason I mention that is to encourage any students who might be reading this to focus more on what they want to do than on the specifics of how. The political economy is constantly shifting such that the jobs titles your parents and professors had may not exist for you (or, if they do exist, the jobs may be very different in character, remuneration and benefits from what they were in the previous generation). In other words, if you ever feel like society doesn’t value or want what you have to contribute, there may still be alternative ways to do your work and to make your contribution, even if it’s not with the job title you thought it would be when you were growing up.

This is a bit of a follow-up on the previous question. I am trying to get of sense of this: you started at some point in your life as a harpist. When did that happen and what got you started as a harpist? How did that harpist become the head of Symbolic Sound Corporation?

The harp lessons came about because of a Title 3 grant to the Albuquerque public schools. One day in my middle school orchestra (where I played violin), they asked if anyone who was taking piano lessons wanted to learn to play harp, and I volunteered. It was more of a “Hmm that would be something interesting to try” than any angelic aspirations on my part 🙂 The grant provided six small lever-harps to the public schools and lessons with the harpist from the Albuquerque Symphony for six students, one in each grade from 7-12 (I was the one in 7th grade). They needed harpists for the Albuquerque Youth Symphony so they wrote a grant to encourage public school students who were already interested in orchestral music to study harp.

Carla Scaletti in 1983 performing her Lysogeny for harp and MUSIC360-generated tape. Still-frame from a video taken by Scott Wyatt of pieces performed at the 25th Anniversary Concert of the Experimental Music Studios at the University of Illinois

Just as an fyi, in the little town of Sherman, Texas where I grew up, the only person who played harp was a girl who came from the richest family in town because they were the only ones who could afford a harp and the van to take her and her harp to Dallas each week for her specialized harp lessons! The harp was an instrument of the privileged class in my background.

Hahaha, we weren’t the richest family in town, but I consider it a privilege to have grown up in a house where there were books, and a record player, and a tape recorder, and where learning was valued for its own sake and teaching was a highly-respected profession; my parents were both educators and both of them encouraged me to follow my curiosity. It was a privilege to grow up in that kind of an environment (though maybe not in the same sense that you’re using the word “privilege?”) It was also a super strict environment — even my younger brother had a lot more freedom of movement than I was ever allowed, “because he’s a boy” — but intellectually, there were no restrictions, so all of my energies went into the world of music and ideas.

My dad had an Ampex reel-to-reel tape deck and he liked to experiment on me! He was always trying out different mic placements and different ways to record the piano. For fun, we would go to Hudson’s Audio store together and A/B the speakers, always bringing in our own recordings for testing. He was such a regular visitor at Hudson’s, that they would let him bring home various pieces of equipment to test overnight. One night he brought home a Triadex MUSE synthesizer (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triadex_Muse) and handed it over to me; I stayed up all night playing with the settings and recording the sequences on my little cassette tape recorder (my dad didn’t let me use the reel-to-reel for anything but “serious” music) before we had to bring it back to the shop the next day.

I also grew up on family stories that always ended with a moral or a lesson. To give just one example, my dad told me that when he was away at college, my grandfather got sick so my dad immediately came home to take care of him. When my dad walked in the door, my grandfather was furious with him. He stood up, walked over to the window, opened it, and threatened to throw himself out the window unless my dad went back to school; he refused to close window until my dad promised him that he would go back to school and finish his degree.

Looking back, I have to smile at how many times my dad repeated those kinds of stories to me, but I understand why he did it: he wanted to convey just how important education is — and that there is an intrinsic value to learning. He also wanted me to know how much my immigrant grandparents had sacrificed to make it possible for him and for me to be able to realize the dream of going to the university. Sometimes, I still have a sense that any time I have an opportunity to make music or learn something new, it’s not just for me, it’s also on behalf of all my grandparents.

To expand on this with you, for example, in second grade I started taking piano lessons and in fourth grade I started taking violin lessons. I worked quite hard playing traditional music and being in all-state orchestra and the like but at a certain point I started to move towards the person who went to Illinois and studied with Scott [Wyatt] and Herbert [Brün] and did what I do. There was a path I went on – what was yours?

I grew up thinking that I would be a scientist. My parents thought that music was part of a balanced life, but not a profession. They didn’t anticipate how intensely I would get into music, or the school orchestra or that I would volunteer to study the harp or especially that I would get obsessed with electronic music.

I had a really cool first piano teacher named Paul Muench who played in a jazz combo and taught group lessons at his piano store. He taught us music theory as part of our lessons (that was my favorite part). One day, he asked, “Who’s brave?” and I raised my hand. He said, “If you play this piece without any mistakes, I’ll give you a dime.” And I did (my first time earning money for performing). From then on, every time he asked who was brave, all six girls’ hands shot up immediately. He hated shy performers and trained us to always have something ready to play at any moment. He was a brilliant, intense pianist — and he died in an accident at an air show doing stunt flying in his antique prop plane.

After I “graduated” from the group lessons, I started taking lessons from the piano professor at the University of New Mexico who would give private lessons in his home on Saturdays. He would accept new students only if they agreed that they did not want to become concert pianists. Since I wanted to be a composer, not a performer, he accepted me. That turned out to be an incredible stroke of luck because George Robert (formerly Katz), came from Vienna where he had studied composition with Anton Webern and piano with Eduard Steuermann (who studied with Schönberg and played piano for the first performance of Pierrot Lunaire). Most of Mr. Robert’s Saturday students were heavily into music of the romantic period, so he was delighted to have a little middle school student who was eager to learn about new music and music theory. As a professor, he was always getting complimentary disks and music, and if he had a duplicate, he would give them to me! One time, he discovered a new piano piece by Shostakovich, and he assigned it to me just so he could listen to it the next Saturday (none of his other students cared about music written after 1900). One Saturday, after my lesson, he said he had a new disk to play for me: it was Steve Reich’s “Come Out.” We stood in his living room listening to the gradual de-phasing, when his wife came in with their little dachshund, Schnatzi, and started screaming at him in German to turn that thing off because it was driving her crazy! He just held up a hand as if to say “wait a moment,” and we finished listening to the piece with her screaming in the background. I always loved sitting in the living room waiting for my lesson, because it was the first house I’d ever been in where there were original paintings on the walls — and there were a lot of them. Sometimes we would get into deep discussion about music and never get to my lesson. It’s hard to picture just how ignorant and naive I was, but one time I asked him why he left a beautiful, musical city like Vienna to come to Albuquerque New Mexico; he looked at me for a moment, considering how he should answer, and then just silently shook his head.

You may not have expected a strong Viennese influence on music students in Albuquerque New Mexico, right? But Kurt Frederick, who started the Albuquerque Youth Symphony and conducted the Albuquerque Symphony and the UNM symphony, was also part of the diaspora. He introduced us to Mahler, Strauss, Penderecki and more. Unlike George Robert, though, he seemed perpetually disappointed in how ill-prepared and uneducated we all were. The phrase I remember him muttering to the orchestra most often was “This is a disaster!” Everyone was terrified of him. When we played Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder, he decided to combine the glockenspiel and the harp parts into one and handed me the extracted part which he had penciled on manuscript paper. Throughout the rehearsal, he yelled at me, berating me for coming in early. I finally figured out that when he had extracted the part, he had accidentally left out a measure. I never said anything about it; I just checked out the score from the library, corrected the pencil manuscript, and played it correctly after that. From then on, I was never intimidated by him (or of any other conductor) again.

When I was in high school, I attended a seminar at the University by John Donald Robb along with my friend Mary Ann. Robb was an attorney, a composer, and music folklorist who attended the first workshop by Bob Moog (Pauline Oliveros and Dick Robinson were also at that workshop) and was one of the first people in the world to own a Moog synthesizer. Robb played his electronic pieces at this seminar and when I heard the synthetic voice in his piece “Rima of the Jungle”, I was hooked! I knew that was the kind of music I wanted to make.

At the University of New Mexico, I continued studying with George Robert and studied composition with Scott Wilkinson (who had studied at Mills with Milhaud). Rather than giving us free rein to compose whatever we wanted, Scott would give us musical “puzzles” to work out; I loved that way of learning composition. Scott came to UNM by way of New York, where he had worked for G. Schirmer publishing house before he came to Albuquerque for health reasons; in Albuquerque, he opened a sheet music bookstore called Music Mart and UNM hired him to teach music theory. Scott was the first person I knew who talked about composing as a profession (up to that point, everyone I knew viewed it as an avocation or a hobby that you could do in parallel with your “real” work).

While I was at UNM, a visiting composer from New York named Max Schubel (he was also the founder of Opus One Records) arrived for a week of teaching and recording sessions, and he hired me as his assistant (and as a harpist) for those recording and editing sessions. He had an unusual approach to recording, which was to get the ensemble to play just a few bars at a time, recording multiple takes of each segment. It was my job to walk into the concert hall, announce the take, and run back into the recording booth to help him catalog the hundreds of takes we were capturing. And, of course, my job included running out for sandwiches and coffee (and eventually for breakfast since the recording and editing sessions would often run all night). My favorite part was watching Max edit all of those takes to produce a single, flawless performance! I got to observe him cutting, and splicing quarter-inch tape for hours. Sometimes, when there wasn’t a good take, he crafted a plausible new take out of the material that he had, even slicing the attack off one note and seamlessly splicing it onto the sustain of another. Watching him, it became gradually became clear to me that tape music was not merely a recording of live music — it was a new art form! I consider his recordings to be compositions in their own right!

Max kept getting invited back to UNM and every time, he would hire me as his assistant and as a harpist for the recordings. On his last visit, he told me to prepare one of my own compositions to be recorded on Opus One (“Motet”). Every summer, Max left New York City to live off- the- grid on a tiny island in Moosehead Lake, Maine, and I would get long letters from him, written in different colored inks, full of advice about life and music, stories about his travails with the vinyl pressing factory or the trouble he had getting the printers to do the florescent ink effects he loved so much, or telling me about the water tower he was building on his island or how I should never move to New York unless I could come there with a huge bag of money. So not only did Max show me the art of splicing tape, he was also a role model for how one could live as an independent artist, composing music and producing new music recordings outside the university.

At UNM, I majored in music, but I also continued taking classes outside of music like calculus and human genetics, and enrolled in the honors program. It was not a conservatory-style education; it was definitely a “research-university-style education.”

And I saw, in electronic music, a chance to bring my interests together. I saw it as a way to study mathematics and science and music. It was a resolution to what, at first, had looked like two conflicting directions. So, I think I was always on this path toward electronic and computer music. There wasn’t a sharp detour or overnight change. It was more like a sequence of choices that kept going toward what was most interesting to me (along with some incredible luck in finding engaging and unique role models and mentors along the way).

When I arrived at the University of Illinois, it was like discovering and reuniting with my long-lost tribe: at the U of I, it was normal to combine music and technology and science and mathematics. You could walk into Treno’s (the cafe right next door to the music building) and have a lively discussion on the ideal computer music language with students, music faculty, and programmers from local software startups. The first week I was there, I remember hearing a radio ad for a store called “Playback — the electronic playground” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4fOWFgCVkYY&feature=youtu.be&t=21s), and I used to walk around campus with that jingle playing in my head. I felt like I had found an electronic playground!

Turning now to the Kyma system, when did Kyma become “a tool others could use” in your thinking (or did you always want it to be something that others could use?) rather than “my personal composition tool?”

Kyma started out as a term paper in a survey of programming languages course and, at first, I thought of it as a composition tool and my own theory of music. But I was a member of the CERL Sound Group, and we were very oriented toward making tools that others could use. CERL was a collection of undergraduate students in electrical engineering and computer science who were building sound-generation hardware and software to work with the PLATO network. Everything developed by the CERL Sound Group went into an open-studio on the same floor as the development offices, so there was always someone in the studio using the hardware and software we were creating next door — graduate students and faculty from the musicology division, high school students from the University High School, engineering undergrads, math majors, and some other random characters (I was never quite sure where they all came from). So, people could use the studio and the developers were right next door, fixing bugs and seeing what it was that people needed in the next release.

So, it was only natural for me to immediately think of Kyma as a language that other people could use too. Very early on, when Kyma still used the Platypus as its audio engine, I gave a Kyma workshop at CERL that was attended by music composition graduate students and even a programmer from Wolfram Research.

And, as you know, I organized the summer Sound Computation Workshops — two-week, intensive bootcamps in sound synthesis and composition using Kyma; people came in from all over the world to attend those workshops and we invited six graduate students from the School of Music to attend for free (that’s when you and I first met!)

Now Symbolic Sound organizes an annual meeting called KISS (Kyma International Sound Symposium) where people report on their research during the day and perform live interactive Kyma compositions each night.

Kyma has been used by both “academic” and “commercial” composers with perhaps the most notable commercial use being the tool for the creation of the voice of “WALL-E.” Have your interactions with composers outside of the academy been significantly different than with those within the academy? What have been some constants that all composers have wanted; what needs have been different?

In the case of WALL-E, Ben Burtt is a sound designer, rather than a composer. Having said that though, the line between sound design and composition is definitely blurred and getting blurrier all the time. When we hear from sound designers, it’s usually when they need something unusual, unique, and amazing — which is both exciting and terrifying, because we usually get contacted after they’ve tried everything else. After trying all the standard plug-ins and traditional solutions, if it seems impossible, that’s when people turn to Kyma. I’m not sure what I think about only getting contacted for the “impossible” jobs, except that, whenever we do manage to help them come up with a solution, it’s a pretty surprising and amazing result, so I guess it is worth the risk.

When you work with a professional sound designer, they are usually at the mercy of a director or a producer who has something vaguely in mind but is unable to articulate what it is that they want. Consequently, there’s a lot of trial and error, where you try to interpret what the director means by phrases like “more organic.” It’s the perennial issue that our society has with sound; people rarely get training in how to listen attentively or analytically, and the vocabulary for describing sound is fairly impoverished. Most people who haven’t had the benefit of musical training find it difficult, if not impossible, to imagine a sound. So, it turns into the cliché of “I don’t know what I want, but I’ll know it when I hear it.”

The primary difference I’ve noticed between academic and non-academic musicians is that those of us who were trained at the university tend to be more word-oriented. We tend to write and discuss and describe and theorize about sound and music; it makes perfect sense that the role of a musician at the university should also be reflective, philosophical and theoretical as well as practical. Whereas many of the non-academic professional musicians I’ve met seem to use sound and music directly, as their native language; they’re always making music, constantly thinking in music, and very often able to pick up a new musical instrument and start making plausible music with it almost instantly. Often, I get the sense that they feel that they might have missed out on something by not going through school; it’s often the case that they were prodigies who were already in demand professionally even before they finished high school, making it difficult to postpone life in order to attend the university.

One thing that is definitely not different between the two groups: there seems to be an equal percentage of highly intelligent, creative individuals in the academic and non-academic worlds. One difference may be that the non-academic people are more likely to be autodidacts (of necessity) which requires a high degree of perseverance and self-motivation. I’ve learned a lot about music, sound design, recording, and other fields from everyone we work with at Symbolic Sound — commercial, non-commercial, professional and avocational alike.

I’ve noticed that I admire and respect the technique of so many composers and musicians — both academic and commercial — often I’m in awe of how well they compose and perform. It’s odd because I don’t feel competitive with them. I think it’s because I enjoy what I do, which is to experiment and explore sounds and ideas and create software structures. It’s not that I’m an uncompetitive person; I just see myself in a different role. And I derive a lot of satisfaction from solving problems posed by the musicians and sound designers using Kyma in addition to the satisfaction I get from making my own music with the system (which, by the way, poses its own problems which demand their own solutions that help keep pushing Kyma forward).

The Pacarana—Kyma’s most recent hardware engine

In your SEAMUS Award acceptance you emphasized the roles of educators and students: “You’re the ones gently shepherding your students out of their comfort zones, opening their minds to new ways of thinking, and problem-solving, and music-making. And you are the students who do the same for your professors.” What do you think makes your hardware and software a good tool for this work? How do you think Kyma is best presented in a creative educational setting in order to accomplish this?

Kyma seems to invite some musicians out of their comfort zones, because it’s based on sounds, rather than on musical notation. Composers like Schaeffer, Stockhausen, Berio and other early tape-music pioneers created a disruption in the linear history of European art music. They created a music that was radically different from anything that came before — it’s music that we can create very directly with sounds, where we can re-arrange time, much in the way a film editor creates a new sequence of time with images. Just as film has become its own art form, independent of live theatre, electronic music is a new branch of music, independent of traditional music.

What’s different about electronic and computer music is not the technology; it’s the radical notion that one can make music directly with sound, without the intermediary of notation or instruments. There are lots of very traditional approaches to music that share the technology of computer and electronic music, but which are simply software models of making music with scores played by instruments. That’s why I prefer the term ‘experimental music’ over the term ‘electronic music’ which refers only to technology and says nothing about the attitude of experimentation. Experimental Music for me, is literally designing experiments, trying out new ways to structure music or to present music or to conceive of music. In some ways, that’s a thankless job, because, by definition, you’ll never become popular since, even if you did, you would be doing something completely different in your next piece. But I’m thankful that some people are doing it. It injects fresh ideas and approaches and sounds into music that eventually find their way into games and films and advertising and even into traditional art music and popular music.

Many people have told me that Kyma changed the way they think about music, that it opened their minds and their ears to a new way of thinking about music.

Usually, it’s the professors who guide their students into new ways of thinking, but because Kyma is set up for autodidacts, a motivated student can dive in and teach themselves and discover new things that they can teach their professors.

Any thoughts that you have had since the SEAMUS conference that you would like to add for us?

Hahaha…I’ve had many thoughts between then and now! 😉

Shortly after SEAMUS, Jeff Stolet invited me out to work with his students at the University of Oregon; Jeff was generous enough to open the workshop to everyone, so I also worked with one of Steve Ricks’ students from BYU, several independent composers who came to Eugene for the concert and workshop, and even some engineers from Google and Microsoft, so there were some fun discussions about deep-learning!

I’ve also been thinking a lot about data sonification and strategies for how we might introduce more “attentive listening” training into public school education which I talked about at ICAD (International Conference on Auditory Displays):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T0qdKXwRsyM&t=1563s

And right now I’m under a deadline to finish a new project with Gilles Jobin (the choreographer/creator of QUANTUM), doing the sounds and music for a new dance piece he’s creating in VR. So, I’ve been immersed in Unity3d and C# scripting on top of doing sound-designing and composing for the project. I’ve been thinking a lot about Virtual Reality, game engines, and about the challenges of collaboratively working on a shared project in the Cloud.

As soon as the VR project is finished, I can focus on the next Kyma International Sound Symposium, KISS2017: Augmenting Reality (http://kiss2017.symbolicsound.com). We’ll be talking about all the new opportunities for sound designers and composers in Augmented, Virtual, and Mixed Reality content creation. We’re also reminding the world that sound and music are the original augmented reality technology! Throughout human history, sound and music have played an intrinsic role in magic, ritual, ceremony, and celebration, transforming the mundane into the sublime, marking everyday events as memorable milestones, and enhancing the flow of experience.

By the way, KISS2017 is open to everyone and it’s a lot of fun, so I hope to see many of you in Oslo in October!

http://kiss2017.symbolicsound.com/

Elizabeth Hinkle-Turner is a composer, author, and researcher who makes her living as the Director of Instructional Information Technology at the University of North Texas. She is the author of the blog afterthefire1964, a resource created for families living through the nightmare and distress of watching a loved one succumb to alcohol and/or drug addiction. An avid martial artist and an (ill-advisedly) aspiring gymnast, she is currently working on a new piece exploring these aspects of her life in connection with electroacoustic music.