by Steven Ricks

Silen Wellington’s when my body becomes the art is a powerful meditation on gender, being trans, and Silen’s decision to start taking testosterone. I was fortunate to see their performance at SEAMUS 2019 in Boston and was immediately struck with several thoughts and questions that I decided to pursue with them via the interview that follows. While my own life experience as a cisgender male and practicing Christian might seem very disconnected from the subjects of Silen’s work, I felt drawn in and touched by their work on both personal and spiritual levels. The questions I pose below clearly don’t cover all the ground projected by when my body… and the subjects it includes, but the answers Silen provides are thoughtful, articulate, and I hope serve to introduce the SEAMUS community and others to their interesting work. To read the text of when my body… and listen to an audio recording of a performance, visit Silen’s website HERE. A few images from the SEAMUS performance are included with this interview. Please enjoy!

SR: How many times have you performed the piece? What were the other venues? How was the SEAMUS venue different (if it was) and how did that affect your performance?

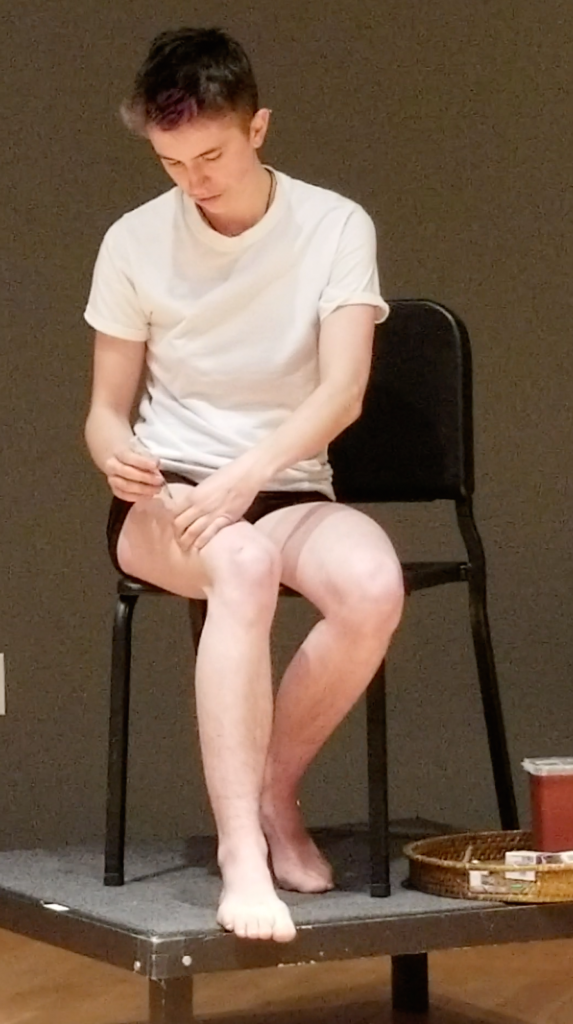

SW: I’ve performed this piece three times now. The first venue for its premier in February 2018 was the Blackbox Theatre on University of Colorado Boulder campus, the second was at SEAMUS at the Boston Conservatory, and the third was for the Playground Ensemble’s 2019 Pride concert at Invisible City, an artist collective space in Denver. While I’ve had different opportunities for lighting decisions at the different venues, the staging hasn’t changed much from performance to performance. Visibility on stage is a consistent problem since I’m usually performing the same height as the audience (which wasn’t the original layout I was planning on for the Blackbox space I premiered the work in). I try to accommodate this by moving parts of my performance further back and using a riser for the injection itself.

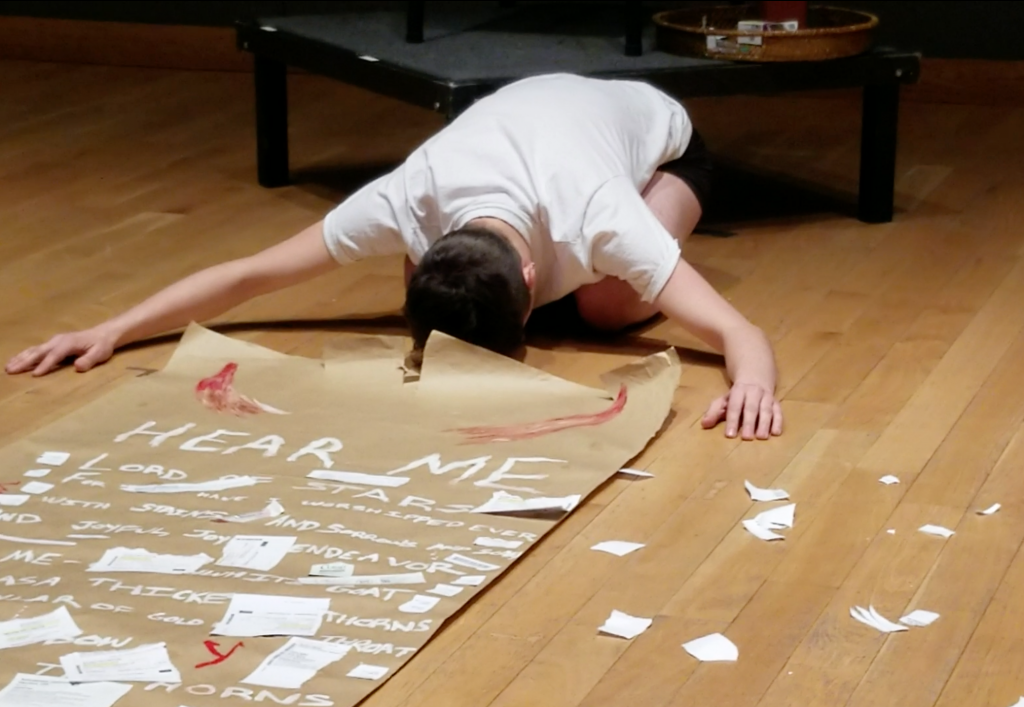

I think more than the venue, the audience of the piece changes how I feel about it. When I first performed it, I invited lots of trans community members, who filled out the first couple rows of the audience. This time, while I brought some (cisgender) guests such as family members, I was performing the piece for mostly cisgender strangers, which changed the level of intimacy for me. While the first time felt like my trans community witnessing me, the SEAMUS performance felt more distanced in some ways, especially that moment when I take my ripped up letter from the therapist and pass it to members of the audience. Literally in that moment, I’m giving away pieces of my medical history to strangers, but for the SEAMUS audience, it also had this quality of asking them to hold those pieces, in part because they don’t belong to me. The medical institutions requiring pathological diagnoses to get trans related health care are not institutions made for or by trans people. As I gave those pieces of the letter in the SEAMUS context, it was almost as if I was saying, “Here, these don’t belong to me – this is yours to heal.”

SR: I don’t know you well, but I infer from your bio in the SEAMUS program and note for when my body becomes the art that your personal journey regarding gender has had a significant impact on your creative work. What aspects of sound in general and/or electro-acoustic music in particular seemed particularly suited to a work exploring the themes presented in when my body…?

SR: I don’t know you well, but I infer from your bio in the SEAMUS program and note for when my body becomes the art that your personal journey regarding gender has had a significant impact on your creative work. What aspects of sound in general and/or electro-acoustic music in particular seemed particularly suited to a work exploring the themes presented in when my body…?

SW: So much of my work is intensely personal. As I started to explore my gender and come into more understanding around being transgender & non-binary, making art about it was a way to process and revolt against the systems that make it difficult to be trans at all. As a composer, sound is incredibly important to me, and the voice is particularly important for trans people, as it’s one of the many ways people gender you, sometimes without even seeing you. As I began to go on testosterone, I was fascinated with how my voice was changing, both in timbre and range, so I wanted to record it, speaking the same poem a few times a week, in large part for my own curiosity. As the recordings piled up, I realized there was a unique opportunity to share my story. Because I had documented so much of my voice transforming, I could share that with people, show them specific points in time that I couldn’t show with acoustic instruments.

Electronic music also allowed me to create different timbral worlds throughout the piece. Sometimes this occurs by layering the recordings of my voice to externalize processes in my own head. To get trans-related health care in the United States, many trans people still need to get a letter from a mental health professional, basically saying they are trans and “stable” enough to go on hormones or seek any other medical transition-related treatment. Early in my piece, I use quotes from my therapist’s letter, things such as “desire to be less feminine,” “a 21-year-old biological female,” “androgynous identity,” “significant mind/body conflict,” “persistent gender nonconforming identification,” and so on. From these quotes I begin to layer my voice from different months of T, creating a cacophony of sound leading up to “diagnosed with gender dysphoria,” which then repeats in an almost granular way. This texture helps recreate the overwhelming quality of my gender process, especially as medically-charged, pathologizing language is thrown onto it, spinning in my head and contributing the seemingly inescapable experience of dysphoria.

Electronics were well–suited for this piece in showing the transformation of that internal world, particularly as I come into ritual and perform an intramuscular testosterone injection. I use multi-delay effects and spatialization to come into a more mystical place as I cast a circle, and I use sounds of waves and consonant, more expansive string samples when I prepare for injection. These textures portray a sense of wholeness and self-love that starkly contrast from the more anxiety-provoking textures of dysphoria.

Additionally, adding my own performance art elements on top of it meant that I could use my physical body in the piece. I knew I didn’t want the piece to only include disembodied recordings of my voice – because that wasn’t what the piece was about, so I made it so my body was part of the art-making, which also allows myself room for the piece to feel different with each performance. Even if I don’t change much of the staging, I’m different every time I perform the piece, and thus, it has a different charge to it. In this way, the piece moves beyond the realm of electronic art, and especially different tropes of electronic music, that often disembody or remove human elements from the art. My work both necessitated electronics and necessitated my human (trans) body.

SR: What ideas for future pieces involving electro-acoustic sound have been inspired or informed by creating and performing when my body…?

SR: What ideas for future pieces involving electro-acoustic sound have been inspired or informed by creating and performing when my body…?

SW: I’m still heavily inspired by spoken word and incorporating it into music, in part because poetry and spoken word are strengths of mine. My most recent electro-acoustic performance art piece was titled body like scripture, which incorporated live spoken word, dancing, and ritual exploring the chaos of dysphoria. In some ways it was a pretty stark contrast to when my body becomes the art. While when my body becomes the art made aspects of my trans journey highly visible and narrative, body like scripture resists legibility. I go back and forth on the issue of legibility in the aesthetics of my trans performance art. Sometimes I make my experience as explicit as possible and that form of legibility feels necessary when still so many people outright deny the existence of trans & non-binary people. Other times, I lean into my illegibility because to become a legible subject can mean assimilating into structures that are largely cissexist, heteronormative, patriarchal, ableist, colonial, misogynistic, capitalist, and racist.

I think for when my body becomes the art, my exposure had a different vein of paradoxical resistance to the tropes of legibility and the trans “reveal,” because even though I was exposing myself in pretty literal ways, I held the power to decide and negotiate those moments of visibility. In future pieces, however, I want to explore the places of incoherence in my trans experience, because so much of it doesn’t operate in cisgender logics. In body like scripture, the text and spoken word is jumbled and chaotic and never explicitly saying “this is what dysphoria feels like” or “here’s how to make sense of it.” So much of my dysphoria and trans experience cannot be explained by language alone. Electroacoustic music will definitely keep informing my work, in part because of its power to create encompassing affective experiences, allowing an audience to feel something even if they don’t know why or how they’re feeling it. For future pieces, I’d love to create a full length trans performance art show that explores issues of legibility/illegibility, coherence/incoherence, survival/resistance, and the sacred/profane, using elements of spoken word, ritual, electroacoustic music, and my body.

SR: Since you started taking T and have been undergoing physical (chemical?) change, have you noticed changes in your perception of sound, artistic/aesthetic impulses, or perhaps anything else that is part of your identity but not typically thought of as being “physical?”

SW: I’m not totally sure how to answer this. For me, it’s pretty impossible to disentangle experiences that are being caused by testosterone alone and experiences that are caused by coming more into who I am (becoming) and who I want to be (become). Explicitly, my gender and my perceptions of gender are not biologically fixed and I don’t think going on testosterone changed them. And, exploring my gender and being in community with other trans folks has changed how I perceive art and music. The more genderful people I meet, the less I’m able to think about them in a cisgender logic. I often joke to my partners that I am a terrible judge of whether or not someone “passes” as cisgender, because I’m always delighting in the beautiful and trans ways of their being. What would it be like to de-gender vocal parts? To write music for trans&queer voices? To embrace trans&queer aesthetics? There is no singular trans aesthetic, but for me, reading queer theory and contemplating what I want my particular trans/queer aesthetic to look, feel like, and do in the world has been much more influential than taking testosterone by itself.

SR: Can you comment more specifically on the spiritual and ritualistic aspects of when my body…?

In addition to being transgender, I also call myself a witch, which I know is a loaded term, but I use it to refer to myself as a practitioner of Earth-based spirituality. For me, going on testosterone was not just a physical decision but also an emotional and spiritual one. Before I knew I was trans, I used to describe my gender experience as an exploration of the land of the feminine, getting to explore in the land of the in-between but pretty firmly having a home in the land of the feminine. As I started to explore drag and realize I was trans, I began a dance in the land of the masculine. Taking T was a way to physically explore this space too. I also want to note that when I use these words “feminine” and “masculine,” I am referring to my personal experience with them, since I don’t believe we can draw any generalizations or “universal” experiences of feminine and masculine.

In “when my body becomes the art,” after I move past the external anxieties of my gender dysphoria diagnosis, I strip myself bare and begin ritual. Drawing on my pagan practices, I cast a circle, invoke the elements and directions, create an energetic container, and pray to Pan, who is an important figure in my exploration of personal masculinity. While there are many ways I do ritual (and most times my rituals are much more verbal), it is important for me to include these ritualistic aspects of the injection. On a personal level, the ritual helps ground me and remember my intention in taking T (which is an ongoing decision made however many times I wish to make it). On a broader level, I think the ritual actually de-emphasizes the physical changes of hormones and medical transition that can often be points of voyeuristic fixation. Instead, it helps portray my gender journey in its full complexity, demonstrating how I enact the ritual of gender on many planes, including the spiritual and physical.