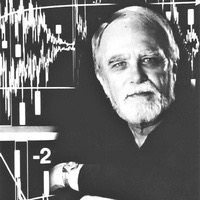

Eulogy of Larry Austin by his daughter, Thais Austin:

Hi, I am Thais. Larry Austin’s middle daughter and fifth child. I was asked today to talk about my father’s work.

Also known as his 8th child. I am not a music professional or colleague or student of my father’s but I am a member of a unique club, the children of the avant garde. We were the observers and spectators to all the experiments, craziness, beauty.

Most people don’t know that our dad’s maternal grandparents were self-taught musicians and actors. Our great grandfather Slim played the trombone for a while in the traveling tent shows. His wife played the piano in those shows and then in the theaters when silent movies put the tent shows out of business. I believe this is where my father got his musical talent.

And in elementary school, when our father was given the opportunity to learn an instrument, he chose the trombone so he could be like Slim. Unfortunately, his arms were too short and he had to settle for the trumpet. This changed his life.

It was the Great Depression. Our grandparents were hardworking people without much money and Vernon, Texas, where my father grew up, was a small cattle community in North Texas. Nevertheless, Dad’s talent was quickly recognized by his teachers, who made sure it was nourished and developed. He was the first person in his family to go to college entering North Texas State University. While at North Texas, he made extra money playing gigs around the Denton area. Truth be told, some of those gigs may have been in what we call now a gentleman’s club.

And he played in the first One O’Clock Jazz band when it was established as part of the first jazz degree program in the world. Our father’s attraction to improvisation and the newest and most experimental types of music started when he was a teenager. While at North Texas, he was greatly influenced by Canadian Composer Violet Archer and wrote his first piece of music. Although he was a talented musician, he put down the trumpet and picked up the fountain pen and started his lifelong career of music composition.

Our father went on to study at Mills College and the University of California at Berkeley before accepting a faculty position at the University of California at Davis. It was the sixties so this is where things got really interesting.

Life for us children of the Avant Garde included concerts almost weekly. A concert series in our living room by artists like John Cage, David Tudor and Karlheinz Stockhausen. For me as a kid, these were great parties where sometimes there were lasers in our yard and we could stay up as late as we wanted. We, of course, thought this was normal.

And Dad even ended up on TV in Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts program along with Aaron Copland. Bernstein loved the piece. Copland said it was not his taste.

The California years were interrupted twice for our family. The first time was when Dad took us to Rome for a year while he was on sabbatical from UCD, and a second time when he based our family in Canada and we performed in a piece my father wrote called the Magic Musicians. We were no Von Trapps but we did perform and sing in Toronto, New York, Chicago and a few other places.

One of our father’s most lasting legacies was the Avant Garde music journal, Source, which he edited and which we, his children, had to spend hours packing for shipment to the subscribers.

In 1972 he accepted a position at the University of South Florida and moved the family to Tampa where he taught until 1978.

He finally returned to Texas, teaching at his alma mater, the University of North Texas, from 1978 until 1996 when he was named Professor Emeritus.

And during all of his teaching years and into his eighties, he continuously composed music, wrote books and articles and mentored colleagues. All of this and his awards and honors are too numerous to mention here. It’s in Wikipedia. But I do want to talk about one of his pieces that meant a lot to my Dad and certainly meant a lot to us: his realization of Ives’s Universe Symphony. I heard it the first time at a performance in Germany. What I remember while listening to it, was how organic it felt. How I could feel the music in my bones. And how our Dad had truly written a masterpiece. I was so proud to have that piece as a family legacy. And when it was performed again at Carnegie Hall with my father as one of the five conductors. I thought about what a special experience it was as a daughter to watch her father conduct his symphony at age 82 on that iconic stage. How many daughters get to do that?

So in the words of Larry Austin, “Music is dead. Long live music.”

Larry Austin is dead. Long live Larry Austin.

From Elainie Lillios:

I served as Larry Austin’s final doctoral graduate assistant at the University of North Texas from 1994-96. I have many memories from that time and the years following, since we remained close after his retirement. One of my responsibilities as Larry’s graduate assistant was serving as UNIX systems administrator for the studios, and most particularly of the NeXTcube that housed the ICMA board email list. That system could NEVER GO DOWN, since the ICMA board list was “absolutely vital” and Larry was very particular about it. I spent many sleepless nights getting the system back up and running after a crash, hoping Larry would never find out that the ICMA board email list went offline. Believe it or not, this was a coveted position at UNT in the mid-90’s; being the caretaker of the ICMA board list was a very important job and one that I took very seriously, along with my other responsibilities, as Larry was quite particular about many things including the tidiness of the studios, and accuracy in concert production. It’s from him that I learned many significant lessons about what it means to be a professional in the field of “computer music.” Among my favorite memories are composition lessons with Larry, where he liked to share anecdotes, especially about his work with John Cage and Merce Cunningham on Larry’s piece Beachcombers. Larry always started anecdotes with “I remember back in 19xx, when I was doing such and such with so and so…” and on the story would go. One of my favorite stories of his was one he liked to tell about meeting people who would ask what he did for a living. He would say, “I’m a composer,” which of course prompted the inquiry “Oh, what kind of music do you compose?” to which Larry would always respond “Why, beautiful music, of course.” Larry leaves behind a great legacy as an electroacoustic composer and mentor. We thank him for his pioneering spirit in creating “Source Magazine” and The Consortium to Distribute Computer Music (CDCM) CD series, and also for his service to ICMA and contributions to SEAMUS and our community at large. Larry certainly had his quirks (who will clear their throat at SEAMUS concerts during quiet moments now?) but was fiercely loyal and dedicated to all of us. He was proud of his colleagues, students, and grand-students, many of whom are now regular contributors to our SEAMUS community. I’m thankful to have been Larry’s student and to have learned from someone who dedicated his life to promoting our music and community. It’s due in great part to Larry’s influence that I am the composer, teacher, and very particular mentor that I am today. May Larry’s memory live on in his music, and in our music as we continue forward in this wide world of sound and experimentation.

From Cort Lippe:

I first met Larry in March of 1975 while he was on the faculty of the University of South Florida in my home town of Tampa, Florida. I was studying composition at Florida State University in Tallahassee and was in Tampa visiting my family. Larry had organized an enormous experimental music festival called “Interface” (at least that is my memory of the festival’s name), that lasted for almost two weeks and included such luminaries as Sal Martirano, Ed London, Joel Chadabe, Stephen Montague, Jerry Hunt and many, many others. The festival had everything: pieces with live electronics, real-time computer music, a wired, interactive dance piece, multimedia, theater, etc. I ended up missing some days of classes to attend every concert, of which there must have been more than 20. Larry starting speaking to me, I guess since he saw me at every concert, and was so friendly and open that I began to think about changing schools to study with him. I managed to make the transfer a year later and spent an intense year studying analog electronic music, computer music, and composition with Larry before he moved to Denton. I wish it could have been longer, but since I took all of his classes, exclusively, (the school was on the quarter system, so I took 4 classes with him the first quarter, and three each in the other two quarters) my contact with him was intense, and included generous invitations to his home, where he and Edna hosted friends, including John Cage and Robert Rauschenberg, among others. As the year progressed, I understood that he was considering a move to Texas, and while I secretly wished he would stay in Florida, I could see that he and Edna were excited about the opportunity. That year was unforgettable, but more importantly, Larry continued to offer me encouragement and support throughout my life. It is impossible to summarize what we learn from our most important teachers, but that year was, to paraphrase the last line of the film Casablanca, “the beginning of a beautiful friendship.”

From Eric Lyon:

It was sad to lose Larry Austin on the cusp of 2019. I first met Larry in Japan in the early 1990s, when he was working at the Kunitachi College of Music. Spatial computer music was a central topic in our initial conversations. Larry was working on multichannel music at the time, along with a set of cityscape pieces based on his Tokyo field recordings. It was a very different approach to computer music than what I was familiar with at the time, even though we were using many of the same tools (Cmix, Csound, rt, and NeXT computers). That first meeting gave me a lot to think about.

I came to know Larry better over the years, and found him to be an intense, super-supportive colleague, and brilliant raconteur with some of the best recollections of avant-garde music and its most colorful characters from the 1960s forward. His editorial work on Source magazine was essential, and remains an important part of his legacy. Larry had a big, brash personality, backed up by deep knowledge of the art and craft of electroacoustic music. He made being an avant-garde composer look like a ton of fun. He was also, I think, a very social composer. It is notable that there were so many homages in his oeuvre, such as “Williams re[Mix]ed” which reworked materials from John Cage’s seminal “Williams Mix,” “Life Pulse Prelude,” based on sketches from Charles Ives’s unfinished “Universe Symphony” (Larry created a performance version of the Symphony itself in 1994), and “SoundPoem/Set,” computer music based on Larry’s recorded conversations with American experimental composers such as Pauline Oliveros and Jerry Hunt. With our loss of Larry, we lose one more connection to the spirit of the mid-20th century avant-garde, which was so different from our current cultural moment.

From Rodney Waschka:

Larry Austin’s thoughts about music and life existed and developed on a grand scale.

As his student, I was constantly surprised and impressed by his way of making big piece after big piece. It seemed to me that he asked himself, “What could music be?” or “What else could music be?” over and over and managed to continually find new and interesting answers to that question. His realization of Ives’ Universe Symphony, his 107-minute Transmission Two: The Great Excursion, for chorus, computer music ensemble, and recorded dialogue, his geographically expansive Canadian Coastlines (performed live for radio with musicians in different parts of Canada), and many other pieces bear witness to his large-scale vision. He also supported the big pieces and big ideas of others. He and Thomas Clark mounted a multi-level performance in the indoor “courtyard” of the Student Union of Cage and Hiller’s HPSCHD for the 1981 International Computer Music Conference (ICMC) at the University of North Texas (UNT). That is one example. In a way, the whole of Source Magazine provides another.

Usually his music had little concern with mere “prettiness”, but sometimes it could be downright gorgeous on many levels. His tribute to Cage, …art is self-alteration is Cage is… is a witty piece of visual art that opens up a luxurious sound world in performance. It also shows his mastery of open form – one of the formal techniques that he utilized in many of his works.

For me to try to recount all of the Larry Austin stories I witnessed or heard Larry (or his wife Edna) tell would keep readers and SEAMUS lawyers up far too late tonight. Some, in a different telling, appear in Thomas Clark’s biography of Austin. There are several stories related to the selection, performance, and recording of his Improvisations for Orchestra and Jazz Soloists by Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic, many stories about Larry’s subversive (and justified) behavior – musical and otherwise, stories about his teaching techniques, his conducting, his interactions with colleagues (Cage, Stockhausen, Feldman, and on and on), heartbreaks (Larry and Edna lost two children), and struggles of various types – from surviving a plane crash to life-threatening illnesses.

SEAMUS readers will know Larry Austin through his electronic and computer music pieces, his founding of the Consortium to Distribute Computer Music (CDCM), his leadership as board member and President of the International Computer Music Association (ICMA), and as the 2009 recipient of the SEAMUS Award.

I will limit myself to one story, that may seem a small thing, but that shows Larry’s dedication to his art, his teaching, and our community of musicians. At the same time that he was President of the ICMA and Director of CDCM, I served as a Research Assistant at the University of North Texas (1988-90). Sales and distribution of the ICMC Proceedings had been moved to the University and I was assigned (among many other duties) to processing and shipping orders. Meanwhile, Larry had converted a bedroom of his house into the shipping center for orders of CDCM discs. So, sometimes I would work in a storage room off the Merrill Ellis Intermedia Theater (MEIT) at UNT on ICMA orders – dealing with payments, pulling stock, boxing, taping and shipping – and other times I would go over to his house in Denton to work on the CDCM orders.

One of the CDCM discs had a misprint on the back tray insert. Fortunately, it was black print on white stock, so Larry carefully prepared a correction that was printed on a larger sticker. In a time-consuming process, after removing the shrink wrap, disassembling the CD case, and taking out the tray insert, one could then cut out an odd-shaped printed correction and finally, cautiously, slowly stick the correction over the misprint, reassemble the CD case, put it through a shrink-wrapper and have a corrected CD ready to ship out.

To my surprise, almost every time I went to work in either location, Larry would show up to help. Of course he mostly knew when I was in his house (sometimes Edna would let me in), but how did he know when I went into that storage room off the MEIT? He would tell me stories of Source, of performances and recordings, of treachery and betrayal, of naiveté and errors on his part; he would talk about his family, and, of course, many times we would just talk music as we worked. His willingness to help with these mundane tasks showed me a dedication to trying to make great art and great artifacts, despite the inevitable mistakes. I often now recognize the same dedication in our musical community, but am disappointed to find so little of it in our financial, educational, commercial, governmental and other institutions. While Larry Austin lived in a musical world of grand scale, he understood the necessary small-scale efforts needed to do fine work and to teach young, naïve, foolish composers.

Austin talking about his completion of Ives’s Universe Symphony, in advance of its premiere by the Nashville Symphony at Carnegie Hall on May 12, 2012.